A podcast about how hormones shape our world.

Latest episode:

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

About Hormonal

Hormones affect everyone and everything: from skin to stress to sports.

But for most of us, they're still a mystery.

Even the way we talk about hormones makes no sense. ("She's hormonal.")

So let's clear some things up. Each week, Rhea Ramjohn is asking scientists, doctors, and experts to break it all down for us.

Subscribe on your favorite platform:

Episodes

- Season 1

- Season 2

Episode 0

August 25, 2020

A Sneak Peek at Season 2

As we work hard on Season 2 of the Hormonal podcast, we’re dropping into your feed with a special request, and a small behind the...

5 min

Episode 1

October 11, 2020

Hot or not? Birth control & sex drive

How birth control affects your sexual desire, self image, and weight fluctuations.

25 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Episode 2

October 19, 2020

The ABC: Abortion & Birth Control

What’s it like to get an abortion and the surprising ways the pandemic is changing abortion access.

34 min

Episode 3

October 26, 2020

The many sides of side effects

Hormonal birth control: positive, negative, and neutral effects

33 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Reproductive choice and reproductive justice

with Dr. Loretta Ross

Episode 4

November 2, 2020

Reproductive choice and reproductive justice

Accessing birth control against the odds

35 min

Episode 5

November 9, 2020

Happy birthday, birth control

Controversy and celebration on the 60th anniversary of the pill

42 min

Episode 7

November 23, 2020

Risky business: birth control during COVID-19

COVID-19 is changing how we access birth control

30 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

with Lynae Brayboy, Amanda Shea & Hajnalka Hejja

Episode 8

November 30, 2020

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

Clue’s Science Team busts your birth control myths

37 min

Credits

Season 2

Executive Producer: Kassandra Sundt

Host: Rhea Ramjohn

Editorial Help from: Amanda Shea, Steph Liao, Nicole Leeds

Clue Design: Marta Pucci & B.J. Scheckenbach

Web Team: Yomi Eluwande, Jane Parr-Burman, Maddie Sheesley

Special Thanks: Trudie Carter, Ryan Duncan, Aubrey Bryan,

Claudia Taylor, Léna Calvarin, Lynae Brayboy

Mixing and recording help from: Bose Park Productions & Rekorder Studios in Berlin.

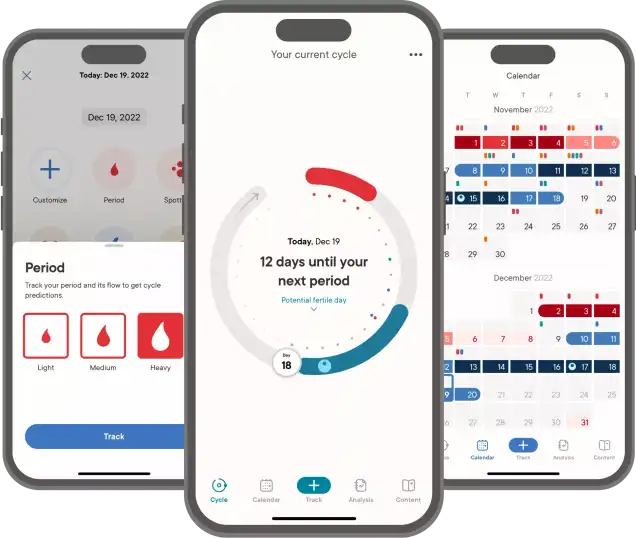

About Clue

Clue is a period tracking app that uses data and science to help women and people wih cycles to understand their bodies. It's also a menstrual and reproductive health encyclopedia.

Learn more about the Clue app and check out what Clue is doing to advance menstrual health research.

Rhea Ramjohn,

host of the Hormonal Podcast

Rhea Ramjohn,

host of the Hormonal Podcast

Your Host

The more knowledge we have about our hormones, our medical & menstrual care, and our reproductive rights, the more we empower ourselves and one another.

Hormonal has offered me the true privilege of speaking with people who have the expertise on the scientific knowledge about our hormones and cycles, as well as those sharing their lived experiences, caring for people with menstruation and how, all combined, shapes our lives everyday.

Gathering facts as well as personal stories are so vital to our understanding of our health, our his/herstories, and our cultures. I deem it a privilege because we haven't had many platforms nor opportunities for menstrual health information being broadly accessible.

Episode 8

We are all hormonal

We are all hormonal

Here’s how we can explore the powers of hormones—not just their burdens.

About

Everyone has hormones. But for some reason only one gender is seen as the “hormonal” one. How can we reclaim this term? And how can we explore the powers of our hormones—not just the burdens?

For more we’re joined now by Martie Haselton, the author of “Hormonal: The Hidden Intelligence of Hormones.” She’s also a professor of psychology at UCLA. Her book makes the argument that the more we know about our hormones, the more we can harness their evolutionary intelligence to aid our modern day lives.

Transcript

This transcript and interview were edited for clarity.

Rhea Ramjohn: Hi, it’s Rhea Ramjohn and you’re listening to Hormonal, brought to you by Clue. Clue is the period tracking app and menstrual encyclopedia -- where you can find out the answers to questions like: how does my menstrual cycle affect my immune system?

We’ve spent a lot of time this season exploring hormones, where the science was, and where the science is. Today, we’re going to be looking ahead at what our next guest thinks will be the future of hormones. Both in the culture, and in the science.

A quick heads up for this episode. We’re going to be talking about some theories in some parts of this interview — about where we think things might be going. But, as we learned back in episode one, sometimes three testes is not better than two. But we hope you’ll indulge us as we occasionally slide down the rabbit hole of speculation.

Be sure to check out helloclue.com for the most up to date information.

But I want to introduce the guest who’s going to help us peer into this crystal ball. Martie Haselton is a professor of psychology and communication at UCLA and she's also the author of the book, "Hormonal: How hormones drive desire shape relationships and make us wiser." So, obviously, we had to reach out to her for the podcast.

Martie thanks for joining us on what’s probably a familiar sounding podcast: Hormonal!

Martie Haselton: Hi I'm so glad to be here.

Rhea: We're so glad to have you. As you know Hormonal is the name of our podcast. And it's also the first part of the title of your book. So let's talk about that.

Martie: Yes. So that, it's the title of my book. And I chose that title because I thought that rather than thinking about “hormonal” in a negative way, we should take it back and think about it in a positive way.

Rhea: Yeah. I wanted to talk about that word hormonal itself. I think for us it's still a kind of slur or derogatory term that's flung about, were you attempting to reclaim the word that way?

Martie: I wanted to. Yes. I definitely want to and so one of the things that we can ask ourselves is what do people mean by hormonal? What's the scientific basis for that? And is there any sexism involved? Those are the kinds of questions that I wanted to confront head on.

So you know, first of all it's definitely a female term, right? Would you ever call a man hormonal? Probably not. And you certainly wouldn't mean the same thing is what you would mean for a woman. So, that was an important starting point because men are just as affected by their hormones as women are. It's just different. Right? So women have monthly cycles and we also go through some really dramatic changes in our hormone cycles if we opt to have kids. And then again later in life. So we you know we have our rev up period in puberty and then our wind down period in menopause. And so there are lots of hormonal fluctuations and they may be in many ways more noticeable for women than for men. But it's not the case that hormones don't affect men. So we kind of need to step back for a moment and ask: Well, what's going on with women what's going on with our view of how hormones affect women's behavior and what are the scientific and practical insights that we can gain from that?

Rhea: And keeping on the subject of the title of your book, that subtitle: “how hormones drive desire, shape relationships and make us wiser.” What did you mean by hormones making us wiser?

Martie: Well this is precisely the point. So our hormones have endowed us with an evolved intelligence. So, we co-evolved with our hormones over millennia, many hundreds of thousands, millions of years even if we think back into the deep ancestral past. And so the idea that many people have that being hormonal means that we've like gone a little crazy and that we've lost our rational faculties and are no longer thinking logically or rationally, is I think backwards. I think we need to reframe it and ask ourselves well how did our hormones evolve to collaborate with our brains in order to produce the behaviors that made our species so successful. And there were a lot of challenges for ancestral women and our hormones were an important part of guiding us through many of those challenges.

Rhea: So our hormones evolved to send us certain signals about big challenges and these challenges may not mesh so well with our modern world. For example, you've written in your book that PMS may in fact serve a purpose? Could you please expand on that? Inquiring minds need explanations for PMS.

Martie: So, when people use the term hormonal they are often referring to those premenstrual days, right? And I think there are a variety of reasons why that is particularly noticeable, including that it is marked by something that is concrete and observable at least by the woman herself, which is her menstrual period starting. So she notices that she feels a little differently on a few days and then boom she gets her menstrual period, she says, “Oh, OK. That is a premenstrual phase phenomenon that I just experienced.” So we tend to notice those hormone shifts in particular for exactly that reason.

Now, premenstrual days also have gotten kind of a bad rap. Right? You know PMS it is sort of like the ultimate example of women being derided as not being rational. And I think that you know we should turn that around or at least we should give that question some serious thought.

So you know might it be the case that along with all of these other hormonally intelligent things that we do, something interesting is happening just as our bodies are preparing for a new menstrual period. And one possibility is that in the ancestral past if you were having regular sexual intercourse with your partner and you were not becoming pregnant, so that menstrual period is arriving again and again and again, then that could be signaling to your body that something's not right with this partner. So a woman's own fertility problems aside, which is certainly a possibility, it could be that she's reproductively or somehow fertility related-ly incompatible with her mate or it could that be her partner is not fertile himself. And so that she might become a little bit more critical of her relationships on those few days leading up to a new menstrual period. You know, that could have served our ancestors well, so she might notice more flaws in her partner she might think, “I'm not so satisfied with this relationship.” If we rethink it in that way then this is no longer premenstrual syndrome. It's premenstrual strategy. Potentially. So time to consider a new mate. Perhaps.

This is fanciful armchair theorizing at present which means there is no evidence for this whatsoever beyond my conjecture with you right now.

So, I think that we really need to interrogate this question. That would be a very academic-y way to say that, that we need to ask ourselves whether people's common views about PMS are actually right and potentially reframe it so that we can ask scientific questions about what the function might be of PMS, whether it serves us in the modern world or not. By understanding what its function might be, we could gain some insights into who experiences PMS when is it more severe and so on.

Rhea: From an evolutionary standpoint when you're talking about hormones from an evolutionary standpoint, does this mean that my body punishes me for not getting pregnant?

Martie: Oh, I wouldn't, I wouldn't say that I would just say that the one thing to bear in mind when we're thinking about evolutionary explanations is that what serves us now in the modern environment might be very different from the endowment that Mother Nature has given us.

But the sort of hormonal nudge that we experience in some cases might be inconsistent with that. And this is one of the major insights I hope that women can gain from reframing how we're thinking about the term “hormonal,” and that is by understanding that although there is this adaptive intelligence, this deep intelligence that we can understand and respect more if we understand it better.

By understanding that these functions were tied to challenges in the ancestral past that we might not be confronting in the modern world, we can decide whether we're going to indulge those hormonal nudges or not and we have better information about whether that's a good idea.

So here's an example. If you are all of a sudden noticing, so let's say you're in a happy long term relationship and you all of a sudden noticed that your attraction to another person, let's say a woman's attraction to a man, she suddenly notices that she's attracted to this other guy at work and maybe she even notices that it's happening and it's happened a couple of times on those few days during the center, they’re in the middle of the cycle around ovulation. Maybe she's using the app and so she knows more about her body and when ovulation occurs than the average person.

So does that mean that she is not in love with her partner and that she's not in a great long term relationship that will make her happy? It doesn't necessarily mean that. It means that this is something that crops up that served our ancestors in some way, maybe it helped her ensure her own fertility if she's not reproducing with her partner then that there's a little signal in there from the body that says, “Hey, what's going on here we're supposed to be reproducing. This is, you know, the reproductive agenda here! We are biological organisms!”

But if she recognizes that then just say, “Oh, I know what that is. That's this relic of the ancestral past. It doesn't necessarily serve my modern woman goals and I'm going to ignore that.” Or alternatively she'll say, "Mmm. Just like the chocolate cake I had for breakfast, I'm going to indulge that and see how fun that is." That's a big decision. That's her decision. But I think knowing something about where the hormonal nudge comes from probably helps her make better decisions about what to do.

Rhea: I love the chocolate cake for breakfast idea. By the way.

Martie: You know it's not like a good idea every day. But sometimes it might just be exactly what we might like to have.

[SPONSOR BREAK]

Announcer: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. The period tracking app, and menstrual health encyclopedia, that takes YOUR cycle seriously.

Clue works every day to counter the stigma and the culturally delivered negativity that affects people with cycles as we go through life.

How do we do it? With our secret weapon: science.

Melissa: So the app for me is just kind of like an entry point.

Meet Melissa. She’s an engineer who works on the Clue App.

Melissa: On the surface it is an app where people track their period. But the bigger vision of pushing female health forwards and having it higher on peoples’ agendas, in peoples’ mind, kind of killing the taboos around menstruation and yeah that's kind of my personal mission working at clue.

Announcer: To support the science-backed app that you know and love, subscribe to Clue Plus. It funds the work here at Clue, the period tracking app that doesn't sell your data, doesn't show you a bunch of ads, and was founded and is led by women.

For more information -- check out Clue.Plus

Alright, back to the show.

[End of Sponsor Break]

Rhea: Your book also highlights the fact that men were for a long time considered the default biomedical sex. Could you expand on that, especially in the ways that that has shaped our understanding of hormones?

Martie: Okay. So, in biomedical research, researchers want everything to be strictly controlled. You want everything to be the same so the only factor is whatever this new thing is that you're investigating, maybe it's a drug to treat the common cold. So you want everything to be exactly the same except for that.

What researchers noticed was that females were kind of messy in that situation because females had hormone cycles which caused them to vary day by day. So rats, lab rats, right. The ultimate research subject, they run in their wheels more on fertile days of the cycle. So that is from a scientist's perspective that is “nuisance,” “noise,” that we want to get rid of. And so because people thought that sex differences, well to the extent they exist, you know, certainly they don't exist at the very basic physiological level, they're not that important. And so we can just study guys. We need to study the males of these various species and we can generalize the information to females.

Now of course the problem with that is we now understand that even down at the cellular level, there are things that operate differently in males and females, so the idea that we can use males as the default, the go-to sex, in order to do this biomedical research is wrong. And we are somewhat behind now because that was the stance that a lot of scientists took. That's been changed here in the United States where the National Institutes of Health now requires that unless you have a very good reason, for example you're studying ovaries or testes in which case you can only study females or males, you have to have a very good reason for excluding one sex from your experiment.

But we're playing catch up and so that means that we're probably behind a little bit. I think there's also been a slower recognition that hormones have important effects on our behavior than I certainly would like to see as a scientist who's writing about these issues and studying them myself.

So humans have sex throughout the cycle, right? We have what is called extended sexuality and we have it to an extreme extent. So we don't just have sex on fertile days of the cycle. We have sex all the time. Whereas other species such as rodents, hamsters is a great example. They will only have sex on fertile days of the cycle and hamster females even grow, what researchers call an “imperferate membrane” across the vaginal canal which prevents males from having sex with them. So it's except on those fertile days of the cycle. So humans look different from that. And for that reason people thought that humans had been “released” or “emancipated” from hormonal control and so it wasn't that important to study hormones and behavior.

Now, I think that hormonal “control” is too strong of a word I would use something like nudge, a hormonal nudge. I mean certainly there are physiological systems that are under strict hormonal control and there may very well be brain systems and behavioral systems that are under strict hormonal control but most of the social behaviors that we're interested in have multiple factors that cause them, and only one of them is hormones.

So hormones are not going to strictly control behavior but they are certainly going to have effects on behavior. And we are a bit hamstrung in our knowledge because we thought that humans didn't have anything like an estrous cycle in the way we see them in non-human animals and that's one of the major advances that has occurred in human psychology, so human psychological research, in the last couple of decades.

Rhea: And by having men as the default biomedical sex at the very beginning of hormone and menstrual research, what kind of… that bias, what did it mean for the scientific understanding of people who do have menstrual cycles?

Martie: Because males have been studied more extensively than females, we're behind in understanding human females. We’ve got some catching up to do. One example of this is our understanding and treatments of sexual dysfunction in women and in men, and for women we really don't have anything that works. Whereas for men, and this might be a bit of an unfair comparison, but for men the primary problem that men complain about is erectile dysfunction. And we've got that one figured out, right? The little blue pill has fixed that problem. Whereas for women it's maybe a more complex story because women's main complaint is about a simple lack of desire but because we know that hormones and desire are interrelated it's going to be really important to study that directly in order to come up with something that might help women who have this “bedroom complaint.” But we're behind.

Rhea: You advocate for people who menstruate tracking their cycles. Why is that? What kind of advantages do we get from tracking our cycles?

Martie: Well I think it's more self insight. For one thing. There are some practical considerations too. Which is probably where hormone cycling, hormone apps came from, was just a desire for women to be able to predict their periods. And so if you're, you know putting an X, a virtual X in your period tracker app and then it's reminding you: “By the way it's day 26 of your cycle, if you're packing for that weekend trip, make sure that you prepare, you know pack accordingly.”

So that's where I think cycle apps originally came from was that kind of an idea. But then people started to realize that all this other really interesting action occurring at other points in the cycle, including on fertile days of the cycle. And this was in part because of the popularization of research that we were doing in my lab, and in the labs of some of my colleagues, where people were beginning to note that humans have this interesting estrus-like phase that's associated with changes in sexuality. And so knowing those things became interesting to women and gave them the opportunity to kind of hack around their hormones: “Oh, I know that this is the day, this is a period of my cycle where sexual activity feels especially nice to me. So I'm going to plan that weekend trip around that perhaps.”

I mean it's a possibility, or women are trying to become pregnant and boy is this helpful to women who are trying to track their cycles and understand when are the propitious days for sexual activity if they're trying to become pregnant.

Rhea: You've basically said that there are differences between cis-gendered men and cis-gendered women.

Martie: Right.

Rhea: And that we should be acknowledging the differences, that there are differences and that you're asserting that everyone is the same and having the same experiences isn't actually very feminist. I was wondering if you could expand on that.

Martie: That's my opinion. Yeah. I think that to be the best captains of our lives I think we need to have the best kind of information.

And I just think at a basic level as women and as men, we are entitled to know everything we possibly can know about our bodies. I think that is sort of a basic human right to be able to ask those questions and get good information, and certainly to be able to study those things if we're not satisfied with what's already out there. So, I you know I think that saying that, "Oh if it's got a biological explanation then that somehow undermines women and therefore we shouldn’t study it," is wrong.

So, you know, I think that it is a form of sort of scientific denial and scientific simple mindedness to think that not exploring our biology somehow serves our interests as feminists. I think it's exactly the opposite. More information is better and we should demand it.

Rhea:I totally agree. Just to push back on that idea a bit because I'm sure you have critics so perhaps they say that the more we dwell on the differences of people who menstruate the more ammunition we're giving to sexist stereotypes.

Martie: Well, I think we need to confront that had on too, and this is part of the reason why we should reclaim the term “hormonal.” So you know, do hormones make us irrational? No, they don't. Do they have an influence on the behavior. Yes, they do. They have an influence on men's behavior too. And so there's some basic sexism there, potentially, that we need to uncover and combat. So you know, men have a hormone cycle. It is every day. So men have a 24-hour testosterone cycle, testosterone peaks early in the morning just prior to waking. And women who co-sleep with men might be aware of this.

Rhea: Right. Right.

Martie: And then it goes down over the course of the day. Now testosterone in men is associated with things like militant attitudes and aggression. But you know we're not saying: keep a man out of the White House because he's got testosterone cycles!

But whereas we might say something about Hillary Clinton's hormones when she's running for office. So you know I think I think we need to dig into that and call that sexism, because I really think that at some fundamental level it is. And if we're going to say that hormones, somehow compromised women, then we're going to have to say the same thing about men.

Rhea: Absolutely. Thank you so much. Martie Haselton. Author of "Hormonal: How hormones drive desire shape relationships and make us wiser.” She's a professor of psychology and communication at UCLA.

Thank you so, much for joining us Martie on the Hormonal podcast.

Martie: No problem. Happy to do it.

Rhea: And listeners, all of you who have stuck with us all season: Thank you! Danke schoen! While, there is still so much we don’t know about our bodies, here at Clue, we’ll keep pushing for answers.

But in the meantime, just as tracking your period helps you get a little more friendly with your cycle, we hope that this season, you also got a little more friendly with your hormones.

Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. If you like the podcast, subscribe and rate us five stars on your platform of choice. Or find us on social media!

To support the work here at Clue — subscribe to Clue Plus. Every cent goes to fund the work here at Clue — that includes the app and the archives and archives of meticulous menstrual health information on Clue’s website. You can find out more about Clue Plus at Clue.Plus.

Episode 8

November 18, 2019

We are all hormonal

Here’s how we can explore the powers of hormones—not just their burdens.

About

Everyone has hormones. But for some reason only one gender is seen as the “hormonal” one. How can we reclaim this term? And how can we explore the powers of our hormones—not just the burdens?

For more we’re joined now by Martie Haselton, the author of “Hormonal: The Hidden Intelligence of Hormones.” She’s also a professor of psychology at UCLA. Her book makes the argument that the more we know about our hormones, the more we can harness their evolutionary intelligence to aid our modern day lives.

"So you know, first of all it's definitely a female term, right? Would you ever call a man hormonal? Probably not. And you certainly wouldn't mean the same thing is what you would mean for a woman. So, that was an important starting point because men are just as affected by their hormones as women are."

Rhea Ramjohn: Hi, it’s Rhea Ramjohn and you’re listening to Hormonal, brought to you by Clue. Clue is the period tracking app and menstrual encyclopedia -- where you can find out the answers to questions like: how does my menstrual cycle affect my immune system?

We’ve spent a lot of time this season exploring hormones, where the science was, and where the science is. Today, we’re going to be looking ahead at what our next guest thinks will be the future of hormones. Both in the culture, and in the science.

A quick heads up for this episode. We’re going to be talking about some theories in some parts of this interview — about where we think things might be going. But, as we learned back in episode one, sometimes three testes is not better than two. But we hope you’ll indulge us as we occasionally slide down the rabbit hole of speculation.

Be sure to check out helloclue.com for the most up to date information.

But I want to introduce the guest who’s going to help us peer into this crystal ball. Martie Haselton is a professor of psychology and communication at UCLA and she's also the author of the book, "Hormonal: How hormones drive desire shape relationships and make us wiser." So, obviously, we had to reach out to her for the podcast.

Martie thanks for joining us on what’s probably a familiar sounding podcast: Hormonal!

Martie Haselton: Hi I'm so glad to be here.

Rhea: We're so glad to have you. As you know Hormonal is the name of our podcast. And it's also the first part of the title of your book. So let's talk about that.

Martie: Yes. So that, it's the title of my book. And I chose that title because I thought that rather than thinking about “hormonal” in a negative way, we should take it back and think about it in a positive way.

Rhea: Yeah. I wanted to talk about that word hormonal itself. I think for us it's still a kind of slur or derogatory term that's flung about, were you attempting to reclaim the word that way?

Martie: I wanted to. Yes. I definitely want to and so one of the things that we can ask ourselves is what do people mean by hormonal? What's the scientific basis for that? And is there any sexism involved? Those are the kinds of questions that I wanted to confront head on.

So you know, first of all it's definitely a female term, right? Would you ever call a man hormonal? Probably not. And you certainly wouldn't mean the same thing is what you would mean for a woman. So, that was an important starting point because men are just as affected by their hormones as women are. It's just different. Right? So women have monthly cycles and we also go through some really dramatic changes in our hormone cycles if we opt to have kids. And then again later in life. So we you know we have our rev up period in puberty and then our wind down period in menopause. And so there are lots of hormonal fluctuations and they may be in many ways more noticeable for women than for men. But it's not the case that hormones don't affect men. So we kind of need to step back for a moment and ask: Well, what's going on with women what's going on with our view of how hormones affect women's behavior and what are the scientific and practical insights that we can gain from that?

Rhea: And keeping on the subject of the title of your book, that subtitle: “how hormones drive desire, shape relationships and make us wiser.” What did you mean by hormones making us wiser?

Martie: Well this is precisely the point. So our hormones have endowed us with an evolved intelligence. So, we co-evolved with our hormones over millennia, many hundreds of thousands, millions of years even if we think back into the deep ancestral past. And so the idea that many people have that being hormonal means that we've like gone a little crazy and that we've lost our rational faculties and are no longer thinking logically or rationally, is I think backwards. I think we need to reframe it and ask ourselves well how did our hormones evolve to collaborate with our brains in order to produce the behaviors that made our species so successful. And there were a lot of challenges for ancestral women and our hormones were an important part of guiding us through many of those challenges.

Rhea: So our hormones evolved to send us certain signals about big challenges and these challenges may not mesh so well with our modern world. For example, you've written in your book that PMS may in fact serve a purpose? Could you please expand on that? Inquiring minds need explanations for PMS.

Martie: So, when people use the term hormonal they are often referring to those premenstrual days, right? And I think there are a variety of reasons why that is particularly noticeable, including that it is marked by something that is concrete and observable at least by the woman herself, which is her menstrual period starting. So she notices that she feels a little differently on a few days and then boom she gets her menstrual period, she says, “Oh, OK. That is a premenstrual phase phenomenon that I just experienced.” So we tend to notice those hormone shifts in particular for exactly that reason.

Now, premenstrual days also have gotten kind of a bad rap. Right? You know PMS it is sort of like the ultimate example of women being derided as not being rational. And I think that you know we should turn that around or at least we should give that question some serious thought.

So you know might it be the case that along with all of these other hormonally intelligent things that we do, something interesting is happening just as our bodies are preparing for a new menstrual period. And one possibility is that in the ancestral past if you were having regular sexual intercourse with your partner and you were not becoming pregnant, so that menstrual period is arriving again and again and again, then that could be signaling to your body that something's not right with this partner. So a woman's own fertility problems aside, which is certainly a possibility, it could be that she's reproductively or somehow fertility related-ly incompatible with her mate or it could that be her partner is not fertile himself. And so that she might become a little bit more critical of her relationships on those few days leading up to a new menstrual period. You know, that could have served our ancestors well, so she might notice more flaws in her partner she might think, “I'm not so satisfied with this relationship.” If we rethink it in that way then this is no longer premenstrual syndrome. It's premenstrual strategy. Potentially. So time to consider a new mate. Perhaps.

This is fanciful armchair theorizing at present which means there is no evidence for this whatsoever beyond my conjecture with you right now.

So, I think that we really need to interrogate this question. That would be a very academic-y way to say that, that we need to ask ourselves whether people's common views about PMS are actually right and potentially reframe it so that we can ask scientific questions about what the function might be of PMS, whether it serves us in the modern world or not. By understanding what its function might be, we could gain some insights into who experiences PMS when is it more severe and so on.

Rhea: From an evolutionary standpoint when you're talking about hormones from an evolutionary standpoint, does this mean that my body punishes me for not getting pregnant?

Martie: Oh, I wouldn't, I wouldn't say that I would just say that the one thing to bear in mind when we're thinking about evolutionary explanations is that what serves us now in the modern environment might be very different from the endowment that Mother Nature has given us.

But the sort of hormonal nudge that we experience in some cases might be inconsistent with that. And this is one of the major insights I hope that women can gain from reframing how we're thinking about the term “hormonal,” and that is by understanding that although there is this adaptive intelligence, this deep intelligence that we can understand and respect more if we understand it better.

By understanding that these functions were tied to challenges in the ancestral past that we might not be confronting in the modern world, we can decide whether we're going to indulge those hormonal nudges or not and we have better information about whether that's a good idea.

So here's an example. If you are all of a sudden noticing, so let's say you're in a happy long term relationship and you all of a sudden noticed that your attraction to another person, let's say a woman's attraction to a man, she suddenly notices that she's attracted to this other guy at work and maybe she even notices that it's happening and it's happened a couple of times on those few days during the center, they’re in the middle of the cycle around ovulation. Maybe she's using the app and so she knows more about her body and when ovulation occurs than the average person.

So does that mean that she is not in love with her partner and that she's not in a great long term relationship that will make her happy? It doesn't necessarily mean that. It means that this is something that crops up that served our ancestors in some way, maybe it helped her ensure her own fertility if she's not reproducing with her partner then that there's a little signal in there from the body that says, “Hey, what's going on here we're supposed to be reproducing. This is, you know, the reproductive agenda here! We are biological organisms!”

But if she recognizes that then just say, “Oh, I know what that is. That's this relic of the ancestral past. It doesn't necessarily serve my modern woman goals and I'm going to ignore that.” Or alternatively she'll say, "Mmm. Just like the chocolate cake I had for breakfast, I'm going to indulge that and see how fun that is." That's a big decision. That's her decision. But I think knowing something about where the hormonal nudge comes from probably helps her make better decisions about what to do.

Rhea: I love the chocolate cake for breakfast idea. By the way.

Martie: You know it's not like a good idea every day. But sometimes it might just be exactly what we might like to have.

[SPONSOR BREAK]

Announcer: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. The period tracking app, and menstrual health encyclopedia, that takes YOUR cycle seriously.

Clue works every day to counter the stigma and the culturally delivered negativity that affects people with cycles as we go through life.

How do we do it? With our secret weapon: science.

Melissa: So the app for me is just kind of like an entry point.

Meet Melissa. She’s an engineer who works on the Clue App.

Melissa: On the surface it is an app where people track their period. But the bigger vision of pushing female health forwards and having it higher on peoples’ agendas, in peoples’ mind, kind of killing the taboos around menstruation and yeah that's kind of my personal mission working at clue.

Announcer: To support the science-backed app that you know and love, subscribe to Clue Plus. It funds the work here at Clue, the period tracking app that doesn't sell your data, doesn't show you a bunch of ads, and was founded and is led by women.

For more information -- check out Clue.Plus

Alright, back to the show.

[End of Sponsor Break]

Rhea: Your book also highlights the fact that men were for a long time considered the default biomedical sex. Could you expand on that, especially in the ways that that has shaped our understanding of hormones?

Martie: Okay. So, in biomedical research, researchers want everything to be strictly controlled. You want everything to be the same so the only factor is whatever this new thing is that you're investigating, maybe it's a drug to treat the common cold. So you want everything to be exactly the same except for that.

What researchers noticed was that females were kind of messy in that situation because females had hormone cycles which caused them to vary day by day. So rats, lab rats, right. The ultimate research subject, they run in their wheels more on fertile days of the cycle. So that is from a scientist's perspective that is “nuisance,” “noise,” that we want to get rid of. And so because people thought that sex differences, well to the extent they exist, you know, certainly they don't exist at the very basic physiological level, they're not that important. And so we can just study guys. We need to study the males of these various species and we can generalize the information to females.

Now of course the problem with that is we now understand that even down at the cellular level, there are things that operate differently in males and females, so the idea that we can use males as the default, the go-to sex, in order to do this biomedical research is wrong. And we are somewhat behind now because that was the stance that a lot of scientists took. That's been changed here in the United States where the National Institutes of Health now requires that unless you have a very good reason, for example you're studying ovaries or testes in which case you can only study females or males, you have to have a very good reason for excluding one sex from your experiment.

But we're playing catch up and so that means that we're probably behind a little bit. I think there's also been a slower recognition that hormones have important effects on our behavior than I certainly would like to see as a scientist who's writing about these issues and studying them myself.

So humans have sex throughout the cycle, right? We have what is called extended sexuality and we have it to an extreme extent. So we don't just have sex on fertile days of the cycle. We have sex all the time. Whereas other species such as rodents, hamsters is a great example. They will only have sex on fertile days of the cycle and hamster females even grow, what researchers call an “imperferate membrane” across the vaginal canal which prevents males from having sex with them. So it's except on those fertile days of the cycle. So humans look different from that. And for that reason people thought that humans had been “released” or “emancipated” from hormonal control and so it wasn't that important to study hormones and behavior.

Now, I think that hormonal “control” is too strong of a word I would use something like nudge, a hormonal nudge. I mean certainly there are physiological systems that are under strict hormonal control and there may very well be brain systems and behavioral systems that are under strict hormonal control but most of the social behaviors that we're interested in have multiple factors that cause them, and only one of them is hormones.

So hormones are not going to strictly control behavior but they are certainly going to have effects on behavior. And we are a bit hamstrung in our knowledge because we thought that humans didn't have anything like an estrous cycle in the way we see them in non-human animals and that's one of the major advances that has occurred in human psychology, so human psychological research, in the last couple of decades.

Rhea: And by having men as the default biomedical sex at the very beginning of hormone and menstrual research, what kind of… that bias, what did it mean for the scientific understanding of people who do have menstrual cycles?

Martie: Because males have been studied more extensively than females, we're behind in understanding human females. We’ve got some catching up to do. One example of this is our understanding and treatments of sexual dysfunction in women and in men, and for women we really don't have anything that works. Whereas for men, and this might be a bit of an unfair comparison, but for men the primary problem that men complain about is erectile dysfunction. And we've got that one figured out, right? The little blue pill has fixed that problem. Whereas for women it's maybe a more complex story because women's main complaint is about a simple lack of desire but because we know that hormones and desire are interrelated it's going to be really important to study that directly in order to come up with something that might help women who have this “bedroom complaint.” But we're behind.

Rhea: You advocate for people who menstruate tracking their cycles. Why is that? What kind of advantages do we get from tracking our cycles?

Martie: Well I think it's more self insight. For one thing. There are some practical considerations too. Which is probably where hormone cycling, hormone apps came from, was just a desire for women to be able to predict their periods. And so if you're, you know putting an X, a virtual X in your period tracker app and then it's reminding you: “By the way it's day 26 of your cycle, if you're packing for that weekend trip, make sure that you prepare, you know pack accordingly.”

So that's where I think cycle apps originally came from was that kind of an idea. But then people started to realize that all this other really interesting action occurring at other points in the cycle, including on fertile days of the cycle. And this was in part because of the popularization of research that we were doing in my lab, and in the labs of some of my colleagues, where people were beginning to note that humans have this interesting estrus-like phase that's associated with changes in sexuality. And so knowing those things became interesting to women and gave them the opportunity to kind of hack around their hormones: “Oh, I know that this is the day, this is a period of my cycle where sexual activity feels especially nice to me. So I'm going to plan that weekend trip around that perhaps.”

I mean it's a possibility, or women are trying to become pregnant and boy is this helpful to women who are trying to track their cycles and understand when are the propitious days for sexual activity if they're trying to become pregnant.

Rhea: You've basically said that there are differences between cis-gendered men and cis-gendered women.

Martie: Right.

Rhea: And that we should be acknowledging the differences, that there are differences and that you're asserting that everyone is the same and having the same experiences isn't actually very feminist. I was wondering if you could expand on that.

Martie: That's my opinion. Yeah. I think that to be the best captains of our lives I think we need to have the best kind of information.

And I just think at a basic level as women and as men, we are entitled to know everything we possibly can know about our bodies. I think that is sort of a basic human right to be able to ask those questions and get good information, and certainly to be able to study those things if we're not satisfied with what's already out there. So, I you know I think that saying that, "Oh if it's got a biological explanation then that somehow undermines women and therefore we shouldn’t study it," is wrong.

So, you know, I think that it is a form of sort of scientific denial and scientific simple mindedness to think that not exploring our biology somehow serves our interests as feminists. I think it's exactly the opposite. More information is better and we should demand it.

Rhea:I totally agree. Just to push back on that idea a bit because I'm sure you have critics so perhaps they say that the more we dwell on the differences of people who menstruate the more ammunition we're giving to sexist stereotypes.

Martie: Well, I think we need to confront that had on too, and this is part of the reason why we should reclaim the term “hormonal.” So you know, do hormones make us irrational? No, they don't. Do they have an influence on the behavior. Yes, they do. They have an influence on men's behavior too. And so there's some basic sexism there, potentially, that we need to uncover and combat. So you know, men have a hormone cycle. It is every day. So men have a 24-hour testosterone cycle, testosterone peaks early in the morning just prior to waking. And women who co-sleep with men might be aware of this.

Rhea: Right. Right.

Martie: And then it goes down over the course of the day. Now testosterone in men is associated with things like militant attitudes and aggression. But you know we're not saying: keep a man out of the White House because he's got testosterone cycles!

But whereas we might say something about Hillary Clinton's hormones when she's running for office. So you know I think I think we need to dig into that and call that sexism, because I really think that at some fundamental level it is. And if we're going to say that hormones, somehow compromised women, then we're going to have to say the same thing about men.

Rhea: Absolutely. Thank you so much. Martie Haselton. Author of "Hormonal: How hormones drive desire shape relationships and make us wiser.” She's a professor of psychology and communication at UCLA.

Thank you so, much for joining us Martie on the Hormonal podcast.

Martie: No problem. Happy to do it.

Rhea: And listeners, all of you who have stuck with us all season: Thank you! Danke schoen! While, there is still so much we don’t know about our bodies, here at Clue, we’ll keep pushing for answers.

But in the meantime, just as tracking your period helps you get a little more friendly with your cycle, we hope that this season, you also got a little more friendly with your hormones.

Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. If you like the podcast, subscribe and rate us five stars on your platform of choice. Or find us on social media!

To support the work here at Clue — subscribe to Clue Plus. Every cent goes to fund the work here at Clue — that includes the app and the archives and archives of meticulous menstrual health information on Clue’s website. You can find out more about Clue Plus at Clue.Plus.