A podcast about how hormones shape our world.

Latest episode:

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

About Hormonal

Hormones affect everyone and everything: from skin to stress to sports.

But for most of us, they're still a mystery.

Even the way we talk about hormones makes no sense. ("She's hormonal.")

So let's clear some things up. Each week, Rhea Ramjohn is asking scientists, doctors, and experts to break it all down for us.

Subscribe on your favorite platform:

Episodes

- Season 1

- Season 2

Episode 0

August 25, 2020

A Sneak Peek at Season 2

As we work hard on Season 2 of the Hormonal podcast, we’re dropping into your feed with a special request, and a small behind the...

5 min

Episode 1

October 11, 2020

Hot or not? Birth control & sex drive

How birth control affects your sexual desire, self image, and weight fluctuations.

25 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Episode 2

October 19, 2020

The ABC: Abortion & Birth Control

What’s it like to get an abortion and the surprising ways the pandemic is changing abortion access.

34 min

Episode 3

October 26, 2020

The many sides of side effects

Hormonal birth control: positive, negative, and neutral effects

33 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Reproductive choice and reproductive justice

with Dr. Loretta Ross

Episode 4

November 2, 2020

Reproductive choice and reproductive justice

Accessing birth control against the odds

35 min

Episode 5

November 9, 2020

Happy birthday, birth control

Controversy and celebration on the 60th anniversary of the pill

42 min

Episode 7

November 23, 2020

Risky business: birth control during COVID-19

COVID-19 is changing how we access birth control

30 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

with Lynae Brayboy, Amanda Shea & Hajnalka Hejja

Episode 8

November 30, 2020

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

Clue’s Science Team busts your birth control myths

37 min

Credits

Season 2

Executive Producer: Kassandra Sundt

Host: Rhea Ramjohn

Editorial Help from: Amanda Shea, Steph Liao, Nicole Leeds

Clue Design: Marta Pucci & B.J. Scheckenbach

Web Team: Yomi Eluwande, Jane Parr-Burman, Maddie Sheesley

Special Thanks: Trudie Carter, Ryan Duncan, Aubrey Bryan,

Claudia Taylor, Léna Calvarin, Lynae Brayboy

Mixing and recording help from: Bose Park Productions & Rekorder Studios in Berlin.

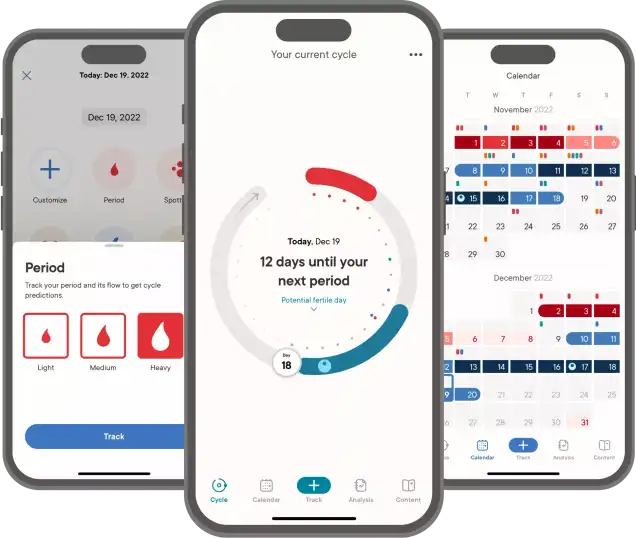

About Clue

Clue is a period tracking app that uses data and science to help women and people wih cycles to understand their bodies. It's also a menstrual and reproductive health encyclopedia.

Learn more about the Clue app and check out what Clue is doing to advance menstrual health research.

Rhea Ramjohn,

host of the Hormonal Podcast

Rhea Ramjohn,

host of the Hormonal Podcast

Your Host

The more knowledge we have about our hormones, our medical & menstrual care, and our reproductive rights, the more we empower ourselves and one another.

Hormonal has offered me the true privilege of speaking with people who have the expertise on the scientific knowledge about our hormones and cycles, as well as those sharing their lived experiences, caring for people with menstruation and how, all combined, shapes our lives everyday.

Gathering facts as well as personal stories are so vital to our understanding of our health, our his/herstories, and our cultures. I deem it a privilege because we haven't had many platforms nor opportunities for menstrual health information being broadly accessible.

Episode 6

How pollutants influence our hormones

How pollutants influence our hormones

Changes in your environment can affect your hormones, and how you feel at different at different points of your cycle.

About

Your endocrine system is a system that relies on balance. An increase or a drop in one hormone can trigger a drop or rise in another. So changes in your environment, like air or water quality, can affect your hormones, and how you feel during different parts of your cycle.

And the changes to your hormones can be even more consequential during critical growth periods — like when a fetus is developing and during puberty.

To discuss this topic and more, we’re joined today by Dr. Shruthi Mahalingaiah. She's a professor at Harvard School of Public Health and a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

Transcript

This transcript and interview were edited for clarity.

Content Warning: In describing one woman’s experience with an unsupportive partner, our guest quotes a story where derogatory terms for a mental disorder were used against a research subject.

Rhea Ramjohn: Hi, it’s Rhea Ramjohn and you’re listening to Hormonal, brought to you by Clue. Clue is the period tracking app and menstrual encyclopedia -- where you can get the answers to all of your questions, like, is my period giving me constipation?

So far on this season of Hormonal -- we’ve talked a bit about how lifestyle can affect your hormone levels. And, that the amount of a given hormone in your body is more like a grain of salt than a cup of sugar.

Because it’s such a sensitive system that relies on balance, any change in our surroundings can have a huge impact. That includes pollution. From the air to the water, contaminants all have unknown potential to impact how the delicate endocrine system functions. And that means pollution can even affect our periods.

For more on this research we're joined now by Shruthi Mahalingaiah. She's a professor at Harvard School of Public Health and a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. Her research looks at how pollution affects hormones.

Shruthi thanks so much for joining us on Hormonal.

Shruthi Mahalingaiah: Thank you so much for having me.

Rhea: So let's set the scene a bit and tell listeners more about why they should care about this. Generally speaking, how does our environment affect our hormones?

Shruthi: So there are many ways the environment can affect our hormones or our menstrual cycles. And I and my research team, we are currently trying to learn more about this process. Some ways that have been shown historically are that some types of pollutants can actually bind hormone receptors. And we have hormone receptors throughout our bodies on almost every kind of tissue you can imagine.

So there are estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors and other hormones thought to be more male type hormones like androgen receptors on many cells in the body. You can imagine that tissues that we know that are hormone responsive like breast tissue, bone tissue, reproductive tissues. If there are other chemicals in our environment that can cross react or bind to hormone receptors this can contribute to or cause dysregulation.

Rhea: And so what's the big headline from your research right now? How does pollution affect menstrual cycles?

Shruthi: The one point I wanted to talk about regarding the menstrual cycle is that it in and of itself is a very sensitive and interconnected function that gets at whole body health. And there are many ways in which our environment might contribute to promoting that health or promoting menstrual cycle irregularity or unpredictability.

One of the key things is that regular menstrual cycles are an integrated function of the hypothalamus and pituitary in the brain talking through hormone-signaling to the ovaries, and there are other endocrine organs that are very important. The thyroid gland and the adrenal glands. So that any deregulation in thyroid or adrenal function or pituitary function can influence menstrual cycle regularity.

Rhea: Wow OK. So from what I'm hearing it sounds as though it's all really connected to everything. I mean you know it reminds me of that song when I was a kid like, “the hip bone is connected to the leg bone,” like it's all connected here, and now with your research connecting it to pollution.

I'm really intrigued and sort of a little scared to find out what's actually going on inside of our bodies. Can you tell me what kind of pollution you're most concerned about?

Shruthi: Thanks. Yes. Everything is interconnected and I think that is one of the big points of our discover. [Our] hormone systems and signaling and our reproductive function is really tied and interconnected to our exposures whether they be in the form of specific pollutants or kind of larger scale types of exposures like stress, perceived stress, crime, things like that.

Am I concerned about one specific thing? I wish I could say that I was, and I wish then we could target that one specific thing and take it out of the universe and then feel super happy, that everything's fine and everything's great. But I don't have one specific thing that I would say, “Do this right now and your period function is going to be amazing!”

I do think that the menstrual cycle is a marker of our health so we can use it to understand whether or not we need to be aware of those changes, maybe interface with the medical establishment or maybe track and put better attention to what we're eating, how we're sleeping, how much exercise we're getting. So you know beyond those factors, some of the pollutants that I've been very interested in are: air pollution and related pollutants from vehicular traffic and greenhouse gases.

I am concerned about persistent organic pollutants as well as some rapidly metabolized, what's called endocrine disruptors -- chemicals that can bind to hormone receptors. One of the things that gives me some hope is that our bodies have intrinsic resilience. And so when we're functioning well sometimes we can use our functions to metabolize and excrete some of these toxicants and with other toxicants, you know newer chemicals, things we don't know all the full whole body effects of, it's going to be harder to know.

My main goal is to increase awareness about this as we're introducing new chemicals and technologies into the environment that may not traditionally be thought to be included in some of our, you know ingestion or air -- like nanoparticles or nanotechnology, fibers that biodegrade. How does this affect the whole ecosystem? And you know if, if it gets concentrated in our water supply or is spewed from a factory. I'd like to have awareness about women's reproductive health in the menstrual cycle included in those discussions as to how to handle those chemicals, and intoxicants.

Rhea: You mentioned persistent organic pollutants. What exactly are those?

Shruthi: Those are pollutants that have a very long half life or take years or decades to biodegrade. So there are a lot of different processes in which our bodies and the earth break down chemicals. Some chemicals are very resistant to that process. And those chemicals that also have endocrine function are a kind of dual threat.

Rhea: So would an example be plastic then?

Shruthi: There are some plasticizers but those typically have shorter half life: some of the persistent organic pollutants are, um, historically used pesticides. PCBs have been used in a lot of different industrial processes. They can bioaccumulate up the food chain and that's just one example molecule.

Older pesticides are like hexachlorobenzene and the antimalarial agent, the mosquito repellent DDT, is another example. And so you know we have to be careful, because there's obviously a risk benefit ratio when we have these very unique chemical discoveries that can actually help short term problems and reduce other kinds of disease risk, like transmitting malaria for example.

And then there's other pharmaceuticals, that depending on their half life, can also be found in our wastewaters and groundwaters. So one thing and I don't mean to scare the readership because we're still learning a lot about this whole process but in...

Rhea: I'm already a little scared, Shruthi.

Shruthi: Oh no. Don't be scared!

Rhea: It's ok, we need the truth.

Shruthi: So what originally was surprising to me is when I was doing my residency and fellowship, I really thought that the uterus and fallopian tubes were this kind of protected black box, an egg would be ovulating and travel down the fallopian tube in this like pristine environment, maternal environment or uterine environment. And the research over time has shown that it's really not protected. It's not a black box. Things that we inhale, for example, aerosolized heavy metals metabolites of tobacco smoking like cotinine, nicotine and some of these persistent organic pollutants as well as short half life pollutants, rapidly metabolized, are found in the fluid surrounding a developing egg. So, our reproductive organs are not an impenetrable barrier.

Rhea: OK yes that is a little bit troubling. This idea that not only is pollution affecting our eyes or lungs -- things that are exposed to the environment. But also, our most intimate internal organs -- our reproductive organs, that’s something that never occurred to me.

Tell us more about this study, I know it isn’t your research, but what do the studies show?

Shruthi: So in one study we looked at air pollution exposure in the high school age range and risk of menstrual irregularity later on in life. And what we found was increased exposure to what's called "total suspended particulate," or the whole amount of air pollution, does seem to influence risk for menstrual irregularity.

So that's an epidemiologic study, so a lot of, a large population of women and the effect estimates were on the order of a couple of percentages to 10 percent. And so it's overall a small percent. But, if you apply it to the general population, with consideration of vulnerable populations, this may affect several women's menstrual cycle function and potentially long term health function in terms of fertility, and other health outcomes like heart disease, diabetes and cardio metabolic risk.

[Sponsor Break]

Announcer: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. The period tracking app, and menstrual health encyclopedia, that takes your cycle seriously.

Meet Melissa.

Melissa: Hi I'm Melissa, and I work in the engineering department at Clue.

Announcer: Melissa is not only an engineer at Clue, but she’s a clue user. She says when working with the Clue science department, as an engineer, she feels a special duty to get things right.

Melissa: I use the app and I know how important that data is for me. And so when I think of the users out there, I can definitely put myself in their shoes. So then I do feel that it is a responsibility to get it right.

Announcer: To support Melissa’s work, and the science-backed app that you trust, subscribe to Clue Plus. It funds the work here at Clue, the period tracking app that doesn't sell your data, doesn't show you a bunch of ads, and was founded and is led by women.

For more -- check out Clue.Plus.

Alright, back to the show.

[End of Sponsor Break]

Rhea: Ok, Shruthi. I want to refocus a bit on your research. What types of pollution are you studying? And what did you find for each of them?

Shruthi: So, I have looked at, most recently, air pollution and I just talked a little bit about what we found in terms of menstrual irregularity. With that same cohort of women, we did find an increased risk of infertility, if you live closer to a major roadway. And again those estimates were on the order of approximately 10 percent. I've looked with several members of my research team into risk of endometriosis and fibroids and we did not find significant increased risk of either.

There are many important considerations when doing this type of research. Most importantly, you know, having the findings replicated. The menstrual cycle hasn't been used in a lot of research and I'm really excited to inspire people to use it as a marker, incorporate it into research studies with the appropriate definition, so that we can have more information on this, you know, to validate or refute some of these initial studies.

Rhea: Yes, please do more of that research. We are dying to know more. Hence the podcast: Hormonal. [laughter]

What kind of pollution has increased in the last 50 years or so? And does that raise concerns for you?

Shruthi: Some of the pollution that I'm specifically worried about right now are around the hormonal activity of personal care products, including makeup cosmetics, hair products, youth creams, things like this that are put on to people's faces. Kids are obsessed with this stuff. They'll smear it on themselves.

You know, what is the endocrine activity? What is the toxicity? And should we be concerned?

A lot of the products that are on the market that promote youthfulness, or age defying qualities, you know, for what we know so far, some of those actually can bind to estrogen receptors to give that estrogen dominant look. Like so, fluffy puffy cells. If you can imagine a pregnant lady: cheeks are slightly flushed, the hair is all luscious and thick, generally speaking, and there is sometimes a little bit of hyperpigmentation in the lips and thickening eyelashes. And so a lot of our makeup products target these things and it's almost like trying to recreate this very hyped up hormonal state.

With collaborators at Harvard School of Public Health such as Tamara James Todd who's done some very interesting pioneering research looking at hair product use and endocrine activity on hormone receptor assays, so cells that are engineered to have hormone receptors and light up when that receptor is bound, has shown that certain products have mixed receptor activity and they're all different.

And of course we're exposed to so many things, it's not just one thing. And so that's one of the things I'm interested in learning more about: the cosmetics and personal care products are generally unregulated. Even though sometimes people are using you know lotions and skin care way more than any other dermal type of topical medication or anything like that.

Rhea: So, if it's still unclear what the effects of skin care products have on our hormones, please for the serum and face mask and eyeliner and makeup lovers and all of us what does that mean?!

Shruthi: So, once I started getting into this I really started reducing my cosmetic purchases. [laughter] And so, yes, what does it mean. It means redefining what you think of as beautiful and really considering what you need to put on your face, in general.

So, I had one of my students look at the top five beauty brands and select one type of cosmetic per face part, like eye, lip, cheek, and kind of collate all of the chemical ingredients in all of the makeup products. And so a couple of things that kind of emerge are coal-tar dyes and siloxanes and like, I don't know, a hundred other chemicals, so it's so hard to say, “What's the one bad thing?” or “What should you cut out?” But I really have started reducing some of my you know eyeliner products, like anything you put on your eyes and it's like kind of like you're getting ready for the burn to kind of go away after the first few minutes. You might want to not use that...

Rhea: Oh no!

Shruthi: But that's just a personal recommendation and you know we don't really have a lot of equivalent testing [like] what people would do if they were taking a drug to market with preclinical and clinical trial testing.

So, I think a lot of different people in the United States are trying to work on how do you get a safer personal care product to market, and working on the legislation around that.

But this gets back to listen to your body. If your eyes are burning after you've put on your eyeliner you shouldn't wear that eyeliner.

Rhea: Yeah, yeah that's a very good point. So back to pollution for just a moment. In terms of the pollutants that you've researched and you've looked at what is most concerning to you regarding hormonal and menstrual health?

Shruthi: So, one of the things from my research that I would be happy to recommend is, you know, if you're going to go on a jog, try not to go on a jog during rush hour on you know a major roadway. Make sure your ventilation system in your home is appropriately maintained. And, if you feel like you've been experiencing irregularity, you should present to see your physician to get a full assessment including a history, a physical hormonal assessment and recommendations therein.

Rhea: Got it. So, if your period is off -- go see your doctor.

And in terms of the everyday pollution that we're exposed to, so not just in makeup for instance, but that all people even those who don't wear makeup. What would you say are the pollutants that are most toxic? Would you say that it's through air pollution, water pollution?

Shruthi: So it depends where that person is in the world and what other risks they are navigating at the time. What kind of governmental structures are in place to reduce emissions, or enhance water quality? Things like that.

So I think that, coming from a country that's historically tried to optimize air quality and water quality, it's a very different kind of recommendation than I have for someone who might be in India using kind of wood burning fuel in their home, exposed to particulates from cooking.

Rhea: Yeah sure. So what about what kinds of pollutants are you most concerned about for people who are living in metropoles like you and I, in Boston, Berlin?

Shruthi: In terms of the key pollutants that I try to avoid in my day to day life: air pollutants and pesticides. I'm pretty confident with our water quality in the Boston area and the water that gets piped into my home, and have monitored those kind of reports.

But my main concern is kind of limiting exposure to dietary related chemicals. And so we do try to buy organic foods and milk, and reduce the chemical burden from what we eat.

Then definitely when we're driving and we're stalled in traffic, turning on like internal circulation only, instead of getting vehicular exhaust pumped right into the car, is something important for me.

So in terms of the air quality we've got air purifiers in all of our kids rooms and try to keep that at the top of our priority list.

Rhea: OK. So who is most vulnerable to environmental changes and pollution when it comes to the menstrual cycle? In terms of for instance age, geography, or socioeconomic status?

Shruthi: That is a great question. So, the times that are really important and that might have much more vulnerability to endocrine disruptors or endocrine active chemicals are times such as the in-utero or prenatal time window. So when a woman is pregnant.

Other times include during adolescence when the hypothalamic, pituitary ovarian axis is undergoing rapid maturation. There, the cells are growing, dividing and becoming functional and that is another concerning time window.

Increasing age and exposure to chemical pollutants is something of a great concern. And there is an emerging literature that suggests our fat cells actually can sequester and hold some of our toxicants, some of those persistent pollutants that we've been exposed to across our lifespan. And some of those chemicals have other chemical properties which make them more attracted to fat or lithophilic. And that may increase risk for obesity. As well as influence the menstrual cycle.

Rhea: Wow. So that’s an important take away. During that prenatal period -- when someone is pregnant -- and during adolescence -- that’s a really vulnerable time.

Keeping that in mind… I'd like to wrap up by pointing out that it seems to me that before your work, menstrual cycles and reproductive health, really hadn't been looked at very closely in terms of pollution. Shruthi, I have my suspicions about why this is. But why do you think that this hasn't really been studied as closely as other health topics?

Shruthi: Oohh. That's an interesting question. I think that the menstrual cycle is gaining a lot of attention now. Obviously women have been having menstrual cycles since you know the origin of the human species.

But, I think it's multifactorial partly from just having the awareness that this is a really key functioning and shouldn't be hidden or shamed. And growing awareness from past literature that the menstrual cycle is a marker of whole body health. And you know women and people with uterus comprise half the population. And it has been unfortunately understudied, and part of that is due to not having awareness potentially, equity, and importance of the menstrual cycle as a key part of the physiology of the body, similar to any other organ system, like the liver or the pancreas.

Rhea: This was a fascinating discussion. You've given us so much information.

Shruthi Mahalingiah, she's assistant professor of environmental reproductive and women's health at Harvard School of Public Health and a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston Massachusetts. Her research looks at how pollution affects hormones.

Dr. Mahalingiah, thank you so much for joining us on hormonal.

Shruthi: Thank you Rhea.

Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. If you like the podcast, subscribe and rate us five stars on your platform of choice. Or find us on social media!

To support the work here at Clue -- subscribe to Clue Plus. Every cent goes towards informing you -- that includes the app and the archives of meticulous menstrual health information on the Clue website. Including the answers to the question at the top of the show. Check the links in the show notes for more.

You can find out more about Clue Plus at Clue.Plus

Episode 6

November 4, 2019

How pollutants influence our hormones

Changes in your environment can affect your hormones, and how you feel at different at different points of your cycle.

About

Your endocrine system is a system that relies on balance. An increase or a drop in one hormone can trigger a drop or rise in another. So changes in your environment, like air or water quality, can affect your hormones, and how you feel during different parts of your cycle.

And the changes to your hormones can be even more consequential during critical growth periods — like when a fetus is developing and during puberty.

To discuss this topic and more, we’re joined today by Dr. Shruthi Mahalingaiah. She's a professor at Harvard School of Public Health and a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

"Things that we inhale, for example, aerosolized heavy metals metabolites of tobacco smoking like cotinine, nicotine and some of these persistent organic pollutants as well as short half life pollutants, rapidly metabolized, are found in the fluid surrounding a developing egg. So, our reproductive organs are not an impenetrable barrier."

Transcript

This transcript and interview were edited for clarity.

Content Warning: In describing one woman’s experience with an unsupportive partner, our guest quotes a story where derogatory terms for a mental disorder were used against a research subject.

Rhea Ramjohn: Hi, it’s Rhea Ramjohn and you’re listening to Hormonal, brought to you by Clue. Clue is the period tracking app and menstrual encyclopedia -- where you can get the answers to all of your questions, like, is my period giving me constipation?

So far on this season of Hormonal -- we’ve talked a bit about how lifestyle can affect your hormone levels. And, that the amount of a given hormone in your body is more like a grain of salt than a cup of sugar.

Because it’s such a sensitive system that relies on balance, any change in our surroundings can have a huge impact. That includes pollution. From the air to the water, contaminants all have unknown potential to impact how the delicate endocrine system functions. And that means pollution can even affect our periods.

For more on this research we're joined now by Shruthi Mahalingaiah. She's a professor at Harvard School of Public Health and a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. Her research looks at how pollution affects hormones.

Shruthi thanks so much for joining us on Hormonal.

Shruthi Mahalingaiah: Thank you so much for having me.

Rhea: So let's set the scene a bit and tell listeners more about why they should care about this. Generally speaking, how does our environment affect our hormones?

Shruthi: So there are many ways the environment can affect our hormones or our menstrual cycles. And I and my research team, we are currently trying to learn more about this process. Some ways that have been shown historically are that some types of pollutants can actually bind hormone receptors. And we have hormone receptors throughout our bodies on almost every kind of tissue you can imagine.

So there are estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors and other hormones thought to be more male type hormones like androgen receptors on many cells in the body. You can imagine that tissues that we know that are hormone responsive like breast tissue, bone tissue, reproductive tissues. If there are other chemicals in our environment that can cross react or bind to hormone receptors this can contribute to or cause dysregulation.

Rhea: And so what's the big headline from your research right now? How does pollution affect menstrual cycles?

Shruthi: The one point I wanted to talk about regarding the menstrual cycle is that it in and of itself is a very sensitive and interconnected function that gets at whole body health. And there are many ways in which our environment might contribute to promoting that health or promoting menstrual cycle irregularity or unpredictability.

One of the key things is that regular menstrual cycles are an integrated function of the hypothalamus and pituitary in the brain talking through hormone-signaling to the ovaries, and there are other endocrine organs that are very important. The thyroid gland and the adrenal glands. So that any deregulation in thyroid or adrenal function or pituitary function can influence menstrual cycle regularity.

Rhea: Wow OK. So from what I'm hearing it sounds as though it's all really connected to everything. I mean you know it reminds me of that song when I was a kid like, “the hip bone is connected to the leg bone,” like it's all connected here, and now with your research connecting it to pollution.

I'm really intrigued and sort of a little scared to find out what's actually going on inside of our bodies. Can you tell me what kind of pollution you're most concerned about?

Shruthi: Thanks. Yes. Everything is interconnected and I think that is one of the big points of our discover. [Our] hormone systems and signaling and our reproductive function is really tied and interconnected to our exposures whether they be in the form of specific pollutants or kind of larger scale types of exposures like stress, perceived stress, crime, things like that.

Am I concerned about one specific thing? I wish I could say that I was, and I wish then we could target that one specific thing and take it out of the universe and then feel super happy, that everything's fine and everything's great. But I don't have one specific thing that I would say, “Do this right now and your period function is going to be amazing!”

I do think that the menstrual cycle is a marker of our health so we can use it to understand whether or not we need to be aware of those changes, maybe interface with the medical establishment or maybe track and put better attention to what we're eating, how we're sleeping, how much exercise we're getting. So you know beyond those factors, some of the pollutants that I've been very interested in are: air pollution and related pollutants from vehicular traffic and greenhouse gases.

I am concerned about persistent organic pollutants as well as some rapidly metabolized, what's called endocrine disruptors -- chemicals that can bind to hormone receptors. One of the things that gives me some hope is that our bodies have intrinsic resilience. And so when we're functioning well sometimes we can use our functions to metabolize and excrete some of these toxicants and with other toxicants, you know newer chemicals, things we don't know all the full whole body effects of, it's going to be harder to know.

My main goal is to increase awareness about this as we're introducing new chemicals and technologies into the environment that may not traditionally be thought to be included in some of our, you know ingestion or air -- like nanoparticles or nanotechnology, fibers that biodegrade. How does this affect the whole ecosystem? And you know if, if it gets concentrated in our water supply or is spewed from a factory. I'd like to have awareness about women's reproductive health in the menstrual cycle included in those discussions as to how to handle those chemicals, and intoxicants.

Rhea: You mentioned persistent organic pollutants. What exactly are those?

Shruthi: Those are pollutants that have a very long half life or take years or decades to biodegrade. So there are a lot of different processes in which our bodies and the earth break down chemicals. Some chemicals are very resistant to that process. And those chemicals that also have endocrine function are a kind of dual threat.

Rhea: So would an example be plastic then?

Shruthi: There are some plasticizers but those typically have shorter half life: some of the persistent organic pollutants are, um, historically used pesticides. PCBs have been used in a lot of different industrial processes. They can bioaccumulate up the food chain and that's just one example molecule.

Older pesticides are like hexachlorobenzene and the antimalarial agent, the mosquito repellent DDT, is another example. And so you know we have to be careful, because there's obviously a risk benefit ratio when we have these very unique chemical discoveries that can actually help short term problems and reduce other kinds of disease risk, like transmitting malaria for example.

And then there's other pharmaceuticals, that depending on their half life, can also be found in our wastewaters and groundwaters. So one thing and I don't mean to scare the readership because we're still learning a lot about this whole process but in...

Rhea: I'm already a little scared, Shruthi.

Shruthi: Oh no. Don't be scared!

Rhea: It's ok, we need the truth.

Shruthi: So what originally was surprising to me is when I was doing my residency and fellowship, I really thought that the uterus and fallopian tubes were this kind of protected black box, an egg would be ovulating and travel down the fallopian tube in this like pristine environment, maternal environment or uterine environment. And the research over time has shown that it's really not protected. It's not a black box. Things that we inhale, for example, aerosolized heavy metals metabolites of tobacco smoking like cotinine, nicotine and some of these persistent organic pollutants as well as short half life pollutants, rapidly metabolized, are found in the fluid surrounding a developing egg. So, our reproductive organs are not an impenetrable barrier.

Rhea: OK yes that is a little bit troubling. This idea that not only is pollution affecting our eyes or lungs -- things that are exposed to the environment. But also, our most intimate internal organs -- our reproductive organs, that’s something that never occurred to me.

Tell us more about this study, I know it isn’t your research, but what do the studies show?

Shruthi: So in one study we looked at air pollution exposure in the high school age range and risk of menstrual irregularity later on in life. And what we found was increased exposure to what's called "total suspended particulate," or the whole amount of air pollution, does seem to influence risk for menstrual irregularity.

So that's an epidemiologic study, so a lot of, a large population of women and the effect estimates were on the order of a couple of percentages to 10 percent. And so it's overall a small percent. But, if you apply it to the general population, with consideration of vulnerable populations, this may affect several women's menstrual cycle function and potentially long term health function in terms of fertility, and other health outcomes like heart disease, diabetes and cardio metabolic risk.

[Sponsor Break]

Announcer: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. The period tracking app, and menstrual health encyclopedia, that takes your cycle seriously.

Meet Melissa.

Melissa: Hi I'm Melissa, and I work in the engineering department at Clue.

Announcer: Melissa is not only an engineer at Clue, but she’s a clue user. She says when working with the Clue science department, as an engineer, she feels a special duty to get things right.

Melissa: I use the app and I know how important that data is for me. And so when I think of the users out there, I can definitely put myself in their shoes. So then I do feel that it is a responsibility to get it right.

Announcer: To support Melissa’s work, and the science-backed app that you trust, subscribe to Clue Plus. It funds the work here at Clue, the period tracking app that doesn't sell your data, doesn't show you a bunch of ads, and was founded and is led by women.

For more -- check out Clue.Plus.

Alright, back to the show.

[End of Sponsor Break]

Rhea: Ok, Shruthi. I want to refocus a bit on your research. What types of pollution are you studying? And what did you find for each of them?

Shruthi: So, I have looked at, most recently, air pollution and I just talked a little bit about what we found in terms of menstrual irregularity. With that same cohort of women, we did find an increased risk of infertility, if you live closer to a major roadway. And again those estimates were on the order of approximately 10 percent. I've looked with several members of my research team into risk of endometriosis and fibroids and we did not find significant increased risk of either.

There are many important considerations when doing this type of research. Most importantly, you know, having the findings replicated. The menstrual cycle hasn't been used in a lot of research and I'm really excited to inspire people to use it as a marker, incorporate it into research studies with the appropriate definition, so that we can have more information on this, you know, to validate or refute some of these initial studies.

Rhea: Yes, please do more of that research. We are dying to know more. Hence the podcast: Hormonal. [laughter]

What kind of pollution has increased in the last 50 years or so? And does that raise concerns for you?

Shruthi: Some of the pollution that I'm specifically worried about right now are around the hormonal activity of personal care products, including makeup cosmetics, hair products, youth creams, things like this that are put on to people's faces. Kids are obsessed with this stuff. They'll smear it on themselves.

You know, what is the endocrine activity? What is the toxicity? And should we be concerned?

A lot of the products that are on the market that promote youthfulness, or age defying qualities, you know, for what we know so far, some of those actually can bind to estrogen receptors to give that estrogen dominant look. Like so, fluffy puffy cells. If you can imagine a pregnant lady: cheeks are slightly flushed, the hair is all luscious and thick, generally speaking, and there is sometimes a little bit of hyperpigmentation in the lips and thickening eyelashes. And so a lot of our makeup products target these things and it's almost like trying to recreate this very hyped up hormonal state.

With collaborators at Harvard School of Public Health such as Tamara James Todd who's done some very interesting pioneering research looking at hair product use and endocrine activity on hormone receptor assays, so cells that are engineered to have hormone receptors and light up when that receptor is bound, has shown that certain products have mixed receptor activity and they're all different.

And of course we're exposed to so many things, it's not just one thing. And so that's one of the things I'm interested in learning more about: the cosmetics and personal care products are generally unregulated. Even though sometimes people are using you know lotions and skin care way more than any other dermal type of topical medication or anything like that.

Rhea: So, if it's still unclear what the effects of skin care products have on our hormones, please for the serum and face mask and eyeliner and makeup lovers and all of us what does that mean?!

Shruthi: So, once I started getting into this I really started reducing my cosmetic purchases. [laughter] And so, yes, what does it mean. It means redefining what you think of as beautiful and really considering what you need to put on your face, in general.

So, I had one of my students look at the top five beauty brands and select one type of cosmetic per face part, like eye, lip, cheek, and kind of collate all of the chemical ingredients in all of the makeup products. And so a couple of things that kind of emerge are coal-tar dyes and siloxanes and like, I don't know, a hundred other chemicals, so it's so hard to say, “What's the one bad thing?” or “What should you cut out?” But I really have started reducing some of my you know eyeliner products, like anything you put on your eyes and it's like kind of like you're getting ready for the burn to kind of go away after the first few minutes. You might want to not use that...

Rhea: Oh no!

Shruthi: But that's just a personal recommendation and you know we don't really have a lot of equivalent testing [like] what people would do if they were taking a drug to market with preclinical and clinical trial testing.

So, I think a lot of different people in the United States are trying to work on how do you get a safer personal care product to market, and working on the legislation around that.

But this gets back to listen to your body. If your eyes are burning after you've put on your eyeliner you shouldn't wear that eyeliner.

Rhea: Yeah, yeah that's a very good point. So back to pollution for just a moment. In terms of the pollutants that you've researched and you've looked at what is most concerning to you regarding hormonal and menstrual health?

Shruthi: So, one of the things from my research that I would be happy to recommend is, you know, if you're going to go on a jog, try not to go on a jog during rush hour on you know a major roadway. Make sure your ventilation system in your home is appropriately maintained. And, if you feel like you've been experiencing irregularity, you should present to see your physician to get a full assessment including a history, a physical hormonal assessment and recommendations therein.

Rhea: Got it. So, if your period is off -- go see your doctor.

And in terms of the everyday pollution that we're exposed to, so not just in makeup for instance, but that all people even those who don't wear makeup. What would you say are the pollutants that are most toxic? Would you say that it's through air pollution, water pollution?

Shruthi: So it depends where that person is in the world and what other risks they are navigating at the time. What kind of governmental structures are in place to reduce emissions, or enhance water quality? Things like that.

So I think that, coming from a country that's historically tried to optimize air quality and water quality, it's a very different kind of recommendation than I have for someone who might be in India using kind of wood burning fuel in their home, exposed to particulates from cooking.

Rhea: Yeah sure. So what about what kinds of pollutants are you most concerned about for people who are living in metropoles like you and I, in Boston, Berlin?

Shruthi: In terms of the key pollutants that I try to avoid in my day to day life: air pollutants and pesticides. I'm pretty confident with our water quality in the Boston area and the water that gets piped into my home, and have monitored those kind of reports.

But my main concern is kind of limiting exposure to dietary related chemicals. And so we do try to buy organic foods and milk, and reduce the chemical burden from what we eat.

Then definitely when we're driving and we're stalled in traffic, turning on like internal circulation only, instead of getting vehicular exhaust pumped right into the car, is something important for me.

So in terms of the air quality we've got air purifiers in all of our kids rooms and try to keep that at the top of our priority list.

Rhea: OK. So who is most vulnerable to environmental changes and pollution when it comes to the menstrual cycle? In terms of for instance age, geography, or socioeconomic status?

Shruthi: That is a great question. So, the times that are really important and that might have much more vulnerability to endocrine disruptors or endocrine active chemicals are times such as the in-utero or prenatal time window. So when a woman is pregnant.

Other times include during adolescence when the hypothalamic, pituitary ovarian axis is undergoing rapid maturation. There, the cells are growing, dividing and becoming functional and that is another concerning time window.

Increasing age and exposure to chemical pollutants is something of a great concern. And there is an emerging literature that suggests our fat cells actually can sequester and hold some of our toxicants, some of those persistent pollutants that we've been exposed to across our lifespan. And some of those chemicals have other chemical properties which make them more attracted to fat or lithophilic. And that may increase risk for obesity. As well as influence the menstrual cycle.

Rhea: Wow. So that’s an important take away. During that prenatal period -- when someone is pregnant -- and during adolescence -- that’s a really vulnerable time.

Keeping that in mind… I'd like to wrap up by pointing out that it seems to me that before your work, menstrual cycles and reproductive health, really hadn't been looked at very closely in terms of pollution. Shruthi, I have my suspicions about why this is. But why do you think that this hasn't really been studied as closely as other health topics?

Shruthi: Oohh. That's an interesting question. I think that the menstrual cycle is gaining a lot of attention now. Obviously women have been having menstrual cycles since you know the origin of the human species.

But, I think it's multifactorial partly from just having the awareness that this is a really key functioning and shouldn't be hidden or shamed. And growing awareness from past literature that the menstrual cycle is a marker of whole body health. And you know women and people with uterus comprise half the population. And it has been unfortunately understudied, and part of that is due to not having awareness potentially, equity, and importance of the menstrual cycle as a key part of the physiology of the body, similar to any other organ system, like the liver or the pancreas.

Rhea: This was a fascinating discussion. You've given us so much information.

Shruthi Mahalingiah, she's assistant professor of environmental reproductive and women's health at Harvard School of Public Health and a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston Massachusetts. Her research looks at how pollution affects hormones.

Dr. Mahalingiah, thank you so much for joining us on hormonal.

Shruthi: Thank you Rhea.

Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. If you like the podcast, subscribe and rate us five stars on your platform of choice. Or find us on social media!

To support the work here at Clue -- subscribe to Clue Plus. Every cent goes towards informing you -- that includes the app and the archives of meticulous menstrual health information on the Clue website. Including the answers to the question at the top of the show. Check the links in the show notes for more.

You can find out more about Clue Plus at Clue.Plus