A podcast about how hormones shape our world.

Latest episode:

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

About Hormonal

Hormones affect everyone and everything: from skin to stress to sports.

But for most of us, they're still a mystery.

Even the way we talk about hormones makes no sense. ("She's hormonal.")

So let's clear some things up. Each week, Rhea Ramjohn is asking scientists, doctors, and experts to break it all down for us.

Subscribe on your favorite platform:

Episodes

- Season 1

- Season 2

Episode 0

August 25, 2020

A Sneak Peek at Season 2

As we work hard on Season 2 of the Hormonal podcast, we’re dropping into your feed with a special request, and a small behind the...

5 min

Episode 1

October 11, 2020

Hot or not? Birth control & sex drive

How birth control affects your sexual desire, self image, and weight fluctuations.

25 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Episode 2

October 19, 2020

The ABC: Abortion & Birth Control

What’s it like to get an abortion and the surprising ways the pandemic is changing abortion access.

34 min

Episode 3

October 26, 2020

The many sides of side effects

Hormonal birth control: positive, negative, and neutral effects

33 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Reproductive choice and reproductive justice

with Dr. Loretta Ross

Episode 4

November 2, 2020

Reproductive choice and reproductive justice

Accessing birth control against the odds

35 min

Episode 5

November 9, 2020

Happy birthday, birth control

Controversy and celebration on the 60th anniversary of the pill

42 min

Episode 7

November 23, 2020

Risky business: birth control during COVID-19

COVID-19 is changing how we access birth control

30 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

with Lynae Brayboy, Amanda Shea & Hajnalka Hejja

Episode 8

November 30, 2020

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

Clue’s Science Team busts your birth control myths

37 min

Credits

Season 2

Executive Producer: Kassandra Sundt

Host: Rhea Ramjohn

Editorial Help from: Amanda Shea, Steph Liao, Nicole Leeds

Clue Design: Marta Pucci & B.J. Scheckenbach

Web Team: Yomi Eluwande, Jane Parr-Burman, Maddie Sheesley

Special Thanks: Trudie Carter, Ryan Duncan, Aubrey Bryan,

Claudia Taylor, Léna Calvarin, Lynae Brayboy

Mixing and recording help from: Bose Park Productions & Rekorder Studios in Berlin.

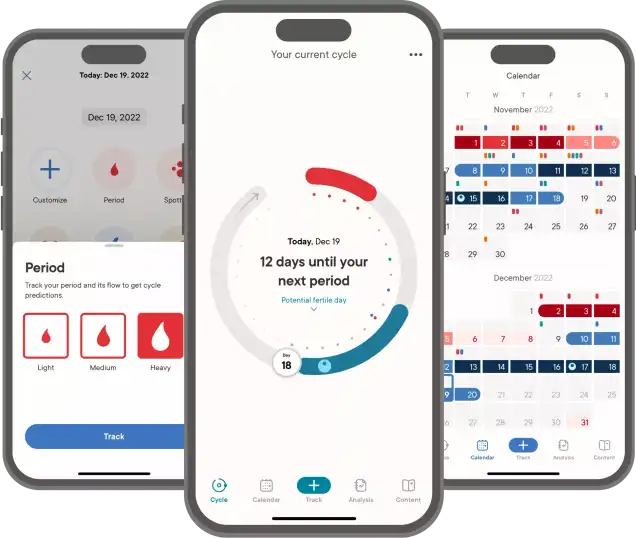

About Clue

Clue is a period tracking app that uses data and science to help women and people wih cycles to understand their bodies. It's also a menstrual and reproductive health encyclopedia.

Learn more about the Clue app and check out what Clue is doing to advance menstrual health research.

Rhea Ramjohn,

host of the Hormonal Podcast

Rhea Ramjohn,

host of the Hormonal Podcast

Your Host

The more knowledge we have about our hormones, our medical & menstrual care, and our reproductive rights, the more we empower ourselves and one another.

Hormonal has offered me the true privilege of speaking with people who have the expertise on the scientific knowledge about our hormones and cycles, as well as those sharing their lived experiences, caring for people with menstruation and how, all combined, shapes our lives everyday.

Gathering facts as well as personal stories are so vital to our understanding of our health, our his/herstories, and our cultures. I deem it a privilege because we haven't had many platforms nor opportunities for menstrual health information being broadly accessible.

Episode 4

Hothouse orchids and dandelions

Hothouse orchids and dandelions

How an exercise craze in the 1980s led to an endocrine discovery.

About

In 1982, Jane Fonda put out her first exercise video. That VHS tape helped spark an exercise craze. But the exercise craze also made a lot of people suddenly lose their periods. Doctors were confused. Was this a temporary reaction due to all the exercise? Was this forever? Were these women still fertile?

Our guest today, Virginia Vitzthum, decided to dig in and research these exact questions. Dr. Vitzthum is the head of scientific research at Clue, and a senior scientist at the Kinsey Institute.

Transcript

This transcript and interview were edited for clarity.

Rhea Ramjohn: Hi, it’s Rhea Ramjohn and you’re listening to Hormonal, brought to you by Clue. Clue is the period tracking app and menstrual encyclopedia -- where you can find out the answer to questions like... can you get pregnant from pre-cum? Spoiler alert: Yes, but,it’s kinda complicated.

Today, we’re going to look at how where and how we live, affects our fertility. Right now, if you were having trouble conceiving, you’d go to a doctor who would measure your hormone levels. If your estrogen or progesterone are too low, that might be a reason you’re having issues.

But, research shows that what’s normal for you, dear listener, on a smartphone or computer in probably an industrialized country, isn’t normal for all people with periods.

In fact, how you live and work, can actually dictate your hormone levels.

But, add in some additional stress, and it can throw your whole cycle out of whack. So today, we’re going to look at some groundbreaking research from the 1980s that followed a new enthusiasm for exercise in industrialized countries.

The question at hand: Why do some people lose their periods when they exercise too much? But some others raised in very hard working conditions don't lose their periods at all?

Virginia Vitzthum is a groundbreaking researcher who set out to answer that exact question. Doctor Vitzthum is the head of scientific research at Clue, and a senior scientist at the Kinsey Institute.

Virginia, thanks for joining us on Hormonal.

Virginia Vitzthum: Thank you for your interest in my work.

Rhea: Well, can you take us back a little bit to the start of that work? Your research all relates to what you call stressors and stress that is “normal for a person.” So what sparked your interest in the relationship between stress and ovulation?

Virginia: Well, it started it really in the 1980s. In the 1980s, there were the beginnings of a real movement to encourage women in the United States and other industrialized countries to really get out there and exercise a lot, to improve their cardiovascular health and other aspects of their health.

But when they did so, and they really like committed themselves to [exercising], they often experienced disruptions in their reproductive functioning, specifically in their ovarian cycles.

They would notice that maybe they wouldn't have a menstrual bleed, or they'd have a very long cycle before having a menstrual bleed, or even go months without a menstrual bleed. And this became very unnerving because of course, these women were concerned about their fertility and they saw doctors, and many of the doctors said, “You'll probably never be able to conceive again. You've got a serious problem.”

But other doctors said, "No, you know, I think that if you stop exercising so much and, or you know, stop dieting,” which was another phenomenon, “that in fact you'll have normal fecundity." Or the capacity to conceive.

And in fact that's what they found. They found that these women could return to the normal capacity to conceive if they reduced their energetic stress. This idea of putting out lots of energy, using lots of energy or consuming or reducing your caloric intake -- those are all energetic stressors, reducing or changing your energy balance.

But the thing is then, that at the same time, there were studies in a couple of populations outside the United States and they found that women in those populations had lower hormone levels and they said, "Whoa, these women working in these really arduous conditions have lower hormone levels. They must be just like these exercising women in the United States who have disrupted cycles and low hormone levels. So these women won't be able to conceive either just like the exercising women.” So that was the parallel that was made.

But this struck me as a paradox, because you had these women in these really hard conditions working a lot, but we knew they were having lots of babies. And so how could their fertility be impaired?

Some people said, “Well, when their hormones go up occasionally during the year then they might be able to conceive, but most of the time they can't conceive.” And that didn't make sense to me. And so I thought [it] was more likely that what was normal stress, the normal vagaries of life [for] these women in these seemingly difficult conditions, were something they were adapted to -- whereas in Boston or Chicago or other such places, these women were used to a really cushy life. And so they wouldn't be able to conceive if they face an unusual stress.

You can kind of think of women in industrialized countries as hothouse flowers. Everything's always really nice and if [you] just make a small perturbation, just a small change in the environment then they can't grow as well until the conditions they were used to return. In these agrarian populations, things were always that hard and they had to reproduce. That's how evolution works. You reproduce under the conditions you've got. And so they were adapted to those conditions physiologically. Well. this is a nice idea but you have to test it. And that was the reason for my study.

Rhea: What what prompted you to actually conduct this study in Chicago and then to choose Bolivia?

Virginia: Well actually I chose Bolivia first and I chose Bolivia because it is what we call a “natural fertility population,” [and] there are periods when they're working really hard in the farms and there are other periods when they don't have much to eat until the crops come in. And so this was a perfect condition under which I could see life long difficult conditions but also short term acute or short term sharp elevations in energetic stress. So, I could look at both conditions at the same time and that's why I chose Bolivia. And I chose Chicago, because it was a typical American population of women living typical, ordinary industrialized lives and was likely to be very similar to what we'd seen in other such populations.

Rhea: So from what I understand, every other day, you measured a lot of pee, and a lot of saliva, to figure out hormone levels at different points in the cycle? Why?

Virginia: So, the the crux of the question was: Was she getting pregnant at the levels of hormones that were low and seemed to be normal in her population? Or could she only get pregnant when the hormone levels were as high as what we saw in Chicago women when they got pregnant?

So that's the critical comparison.

And so if she couldn't get pregnant at typical levels for her population, then one theory was correct, the energetics theory. But if she could get pregnant then the what we call life history theory or my model, I call it the flexible response model, was correct. So, this required that I collect over 10,000 samples of saliva over the course of two years, and God knows how many gallons of pee… and then have them all assayed, and so that was the comparison. And then in the Chicago women we had a sample that self collected their own samples. These were women intending to get pregnant so they self collected their samples and we had a small sample of 30 women there that we could compare our results to.

Rhea: And did, out of curiosity did any of the women in the studies actually get pregnant within those two years?

Virginia: Yes. So the end result of all of that was that [in] the women, I observed more than 60 conceptions, and the outcome of all of this data collection was that I could see the hormone levels at which these women were actually conceiving, and I could see the hormone levels at which the Chicago women were conceiving. And so, I could then see whether or not they only conceived at the same high[hormone] levels or if the Bolivian women were conceiving at lower levels than the Chicago women.

Well that's what I found.

Very surprising to lots of people. These women at their low hormone levels were successfully conceiving and maintaining their pregnancies all the way to giving birth. I followed these women for two years. I knew what their hormone levels were like when they conceived, as their babies developed, and when their babies were born. So I knew exactly what their hormone levels were. And I could compare them to the Chicago women and I could declare legitimately that these women had perfectly functionally adequate hormone levels even though they were lower than Chicago women and they conceived at those low levels.

Rhea: Right. So from the pee you found out when they got pregnant. And from the spit, you knew their hormone levels at the time of conception. And you found that even though these women in Bolivia had lower hormone levels, they still got pregnant at that lower level.

Virginia: And, they conceived without problems. And so what this means is then that there's no species wide normal level of hormone. There's no one correct hormone level that everyone should have in order to be reproductively healthy or reproductively successful.

That in fact every population has different ranges of what is adequate functionally to conceive, and to be healthy, and that we shouldn't assume that white women in industrialized countries are our standard against which to compare everyone else in the world.

And the reason for this is that there are different factors that contribute to your hormone levels. There's going to be individual genes, there's going to be how much energy you expend and intake, there's going to be the composition of your diet and there's going to be other factors that we're just starting to investigate. But those are four of the most important and because those vary across populations. It's perfectly normal and natural that the hormone levels will vary across populations but that women will conceive at those normal hormone levels in their population.

It's also the case that women are responsive to stress that they experience. So it's not like these Bolivian women could tolerate any level of stress. In fact, when we went through the poorest season where they had to work really hard and had little food, then their hormone levels also would dip down and they would also experience reproductive or ovarian cycle disruption. So their bodies are responding similarly across the entire world's population of women but that doesn't mean they have identical hormones.

Rhea: So, you were right! Different groups of people -- depending on their lifestyle -- have different levels that are considered normal for them. Just like, for example, how someone who sits at a cushy desk job might have a different calorie need than a professional athlete. There is no one universal normal.

This makes me think about hormone based medicines. I was wondering how does this information apply to the way women receive health care? Especially in terms of contraception and actually conceiving?

Virginia: These are really important questions because what it means is that we need to have different hormonal contraceptive formulations, for women who are choosing hormonal contraceptives, that fit women.

For too long, the pharmaceutical industry and others have thought that, and the medical world have thought that, basically there's one normal. And so a small set of formulations of hormonal contraceptives would be the best for everyone. But in fact there are women who have said for a very long time, “I get really bad side effects from this combination of pills or this combination of hormones and therefore I'm going to stop using it because it's just too much trouble.” And they've been told, “No, no, no. This is really all in your head. You will adjust your body will adjust and just tolerate it so that you don't have to become pregnant because after all perhaps that's a harder choice to make.”

In fact, what we need to do is recognize that different populations have different average levels and we need to have more formulations that are suited to those women and we can see that in the data as well.

We see that in populations like Bolivia, they have much higher rates of discontinuing use of the hormonal contraceptive in the first year of use due to their reports of side effects. And so it's not just a theory. We've actually seen it in action. And I've been told, for example by a colleague who worked in Bangladesh, that women would actually cut the pills in half to try to reduce the side effects. But of course this has an unknown effect on the risk of pregnancy. So it's not a great idea, it's not a solution.

We need an appropriate formulation and it's not just across populations, it's also within a population. There's more variation in hormone levels within a population than there is across a population. And that may seem very difficult to to really picture in your mind right now. But the differences between say a Boston woman and a Bolivian woman is about 80 percent Bolivians or about 80 percent of U.S. women. But within the population of Bolivian women and within the population of Chicago women or Boston women or German women, the range of variation in normal cycles is five fold. A woman can be perfectly healthy and have only one fifth the hormone level of somebody who's the highest value in that population. So we have lots of variation within and between populations depending on all these different sorts of factors. And we need to instead of telling women that they should fit the pill, we need to fit the pill to the woman. We need to change our attitude.

Rhea: I'm all for that. I love that. That should be the new slogan for menstruating people everywhere. You mentioned energetic stress before. What about the effects of emotional or mental stress on the menstrual cycle?

Virginia: This is an interesting question because it is a very controversial area of research and there's been data on both sides of that question of whether or not there is enough -- whether or not emotional or psychosocial stress can actually affect reproduction.

I favor the idea that it probably does. I think the data that we have is very compelling. In the best studies done, you see it. The fact of the matter is the first person to really document that kind of stress was a fellow named Sam Wasser looking at baboons and the social dynamics among female baboons and positing that there was a real effective psychosocial stress on reproduction in the baboons and he demonstrated it there. And, this makes sense though, it makes sense that energy is of course important. And so as well as energy, are vitamins of various kinds like iodine deficiency can be a factor in disrupting reproductive function. That makes sense because iodine is very important to proper physiological functioning.

Well, we're social creatures, we need support. We need support through pregnancy we need support to give birth, we're the only primate where it is the most common situation is to have someone assisting us in our birth. Whereas other primates can give birth on their own. We always have somebody assisting us whether it's a mother, a partner, another family member, a midwife as we call them today. There's always, just about always, somebody there. It's a myth that women went off into the wild and had babies by themselves because we have a lot of difficulty giving birth. And so that psychosocial support that sense of being supported is very very important in [a] human life cycle. And having it during this period of pregnancy and birthing is really critical. So it makes sense that your body says if you don't have that, maybe it's not a good time for you to reproduce.

[SPONSOR BREAK]

Announcer: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. The period tracking app, and menstrual health resource, that’s not like the other apps.

How is Clue different? Well, Clue doesn’t sell your data.

Instead, as co-founder and CEO Ida explains, the data is separated from your identity, and given to scientists to help push our understanding of menstrual health into the future.

Ida: This is something we have chosen to do because we believe that we have a very unique responsibility when we govern this very unique data set to also help advance research in female health for the benefit of our users but also the greater public. And we have seen that our users share that notion and that they're willing to share their anonymized data so that we can advance female health research.

Announcer: To support the app that doesn’t sell your data and is fighting for BETTER reproductive science, subscribe to Clue Plus.

Your subscription to Clue Plus also funds the period tracking app that doesn't show you a bunch of ads, and was founded and is led by women.

For more -- head over to Clue.Plus.

Alright, back to the show.

[End of Sponsor Break]

Rhea: Virginia, when you were conducting your study, and looking at women in agrarian communities in Bolivia and then women in Chicago and creating this comparison, what differences did you notice in the menstrual cycles of both populations?

Virginia: Yes of course. In the United States and other industrialized countries in the modern world it's the case that women often do not start reproducing, having babies, until sometime in their 20s. But they've had menarche many years before, they've had their first menstrual cycle, menarche when they're perhaps ten or eleven or twelve or thirteen.

So there's this very long span of time in which they're cycling, month after month, year after year and not reproducing because they're not in a sexual relationship. Then they may have a couple of children in their lifetime. They may breastfeed them for a very short time and then they have menopause. And so through that whole span of time they have had perhaps four or five hundred menstrual cycles and experience the hormonal changes of those over the decades of their life.

In contrast, Bolivian women have menarche more around the age of 14 or 15 or 16. They start having babies around the age of 20. And once they have a baby, then they may breastfeed for anywhere from two to four years, have another baby, do the same. And through their life may have as many as 10 or 12 babies. And so they typically in the course of their lifetime, even if it's just as long as an American woman, they may have only 40 or 50 cycles. In fact, there was one woman you know I was asking all the women in these studies when was your last menstrual cycle when I would first interview her, one woman told me when I was 17 and she was 43.

Rhea: Wow.

Virginia: So she had really always continuously been either pregnant or lactating. She was an exceptional case. But you get the idea this pattern of only 40 or 50 cycles versus four or five hundred cycles is the norm throughout our evolutionary history. Women have not experienced four or five hundred cycles they've experienced only 40 or 50 because it was normal to have babies and to lactate them for a long period of time and then to have another baby to have a late menarche and an early menopause compared to what we see today in industrialized countries.

The implications of this for all this hormonal production and exposure are only beginning to be understood. So for example, we have far higher rates of breast cancer in women in industrialized populations than in Bolivian women or other such women in similar populations. We have a high rates of other kinds of hormone related cancers and other sorts of differences in risk for osteoporosis and for autoimmune diseases and for other conditions that are probably a reflection of the fact that we don't have a lot of babies and we have a lot of exposure to menstrual cycling changes in hormone levels.

Now, I'm not advocating that this means we're obligated to go and have lots of babies. That's not the point at all. But it means is to understand what's going on and therefore devise appropriate lifestyle or health interventions that can mitigate those kinds of problems in a way that is not disruptive. That's not over medicalized. There's nothing wrong with women not having babies anymore than there's anything wrong with women having lots of babies. The point is to create the best health for women whatever their decisions are. And we can't do that unless we know more about what's going on.

Rhea: Virginia, You have made some really great points today and an especially compelling argument in this conversation about the need for further research to better understand the endocrinology of different kinds of people who menstruate around the world. But, what other kinds of research do you think is important, moving forward, to make hormonal therapies more effective for more people?

Virginia: Well I do think that to begin with, we need to understand what the causes of all of this variation is. And that means understanding more about the growth of the girl.

We have concentrated a great many resources on understanding children from the time that they're born until about five years of age. And that's logical because that's a period of high mortality. And so a lot of effort has gone into understanding that period of life. And we put a lot of effort into understanding adult women, particularly women who are going to become moms. There's been a real focus on that.

I think that we need to do two things: First of all, we need to concentrate on the growing girl, the girl who is growing from age 5 through about age 18 and those changes that happen through menarche as she becomes a full adult female. It's surprising how little we know even within one culture, the United States or Germany or Europe and other such industrialized countries. And we know so much less in other populations. And we don't understand that period as well as we need to at all.

The other thing is that we need to appreciate the incredible diversity of women's bodies and needs, and to design medications as well as hormonal contraceptives, to design health care, in response to that. We need to recognize that and do more research instead of trying to pigeonhole every woman in to this old fashioned medical view that women are basically biological clocks that should be running on time and running according to calendars. Women's biology is responsive to the environment, responsive to psychosocial conditions, responsive to her activities and it has evolved to be exactly that. And so these are normal variations that occur in response to the conditions that are all around her and her part of her life. And instead we're trying to pigeonhole her into this narrow view of what a woman's body should be like.

Women are not little clocks.

Rhea: That’s right. I totally agree with you, you’ve made me feel completely empowered that I have all of this amazing energy inside my body.

Thank you so much. Virginia Vitzthum. We thank you for joining us here. She's the senior researcher at the Kinsey Institute and the head of Scientific Research at Clue. Thank you so much for joining us on Hormonal.

Virginia: Thank you very much for your time.

Rhea: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. If you like the podcast, subscribe and rate us five stars on your platform of choice. Or find us on social media!

To support the work here at Clue -- subscribe to Clue Plus. Every cent goes to fund the work here at Clue -- that includes the app and archives of meticulous menstrual health information on Clue’s website. You can find out more about Clue Plus at Clue.Plus.

Episode 4

October 21, 2019

Hothouse orchids and dandelions

How an exercise craze in the 1980s led to an endocrine discovery.

About

In 1982, Jane Fonda put out her first exercise video. That VHS tape helped spark an exercise craze. But the exercise craze also made a lot of people suddenly lose their periods. Doctors were confused. Was this a temporary reaction due to all the exercise? Was this forever? Were these women still fertile?

Our guest today, Virginia Vitzthum, decided to dig in and research these exact questions. Dr. Vitzthum is the head of scientific research at Clue, and a senior scientist at the Kinsey Institute.

"You can kind of think of women in industrialized countries as hothouse flowers. Everything's always really nice and if [you] just make a small perturbation, just a small change in the environment then they can't grow as well until the conditions they were used to return. In these agrarian populations, things were always that hard and they had to reproduce. That's how evolution works."

Rhea Ramjohn: Hi, it’s Rhea Ramjohn and you’re listening to Hormonal, brought to you by Clue. Clue is the period tracking app and menstrual encyclopedia -- where you can find out the answer to questions like... can you get pregnant from pre-cum? Spoiler alert: Yes, but,it’s kinda complicated.

Today, we’re going to look at how where and how we live, affects our fertility. Right now, if you were having trouble conceiving, you’d go to a doctor who would measure your hormone levels. If your estrogen or progesterone are too low, that might be a reason you’re having issues.

But, research shows that what’s normal for you, dear listener, on a smartphone or computer in probably an industrialized country, isn’t normal for all people with periods.

In fact, how you live and work, can actually dictate your hormone levels.

But, add in some additional stress, and it can throw your whole cycle out of whack. So today, we’re going to look at some groundbreaking research from the 1980s that followed a new enthusiasm for exercise in industrialized countries.

The question at hand: Why do some people lose their periods when they exercise too much? But some others raised in very hard working conditions don't lose their periods at all?

Virginia Vitzthum is a groundbreaking researcher who set out to answer that exact question. Doctor Vitzthum is the head of scientific research at Clue, and a senior scientist at the Kinsey Institute.

Virginia, thanks for joining us on Hormonal.

Virginia Vitzthum: Thank you for your interest in my work.

Rhea: Well, can you take us back a little bit to the start of that work? Your research all relates to what you call stressors and stress that is “normal for a person.” So what sparked your interest in the relationship between stress and ovulation?

Virginia: Well, it started it really in the 1980s. In the 1980s, there were the beginnings of a real movement to encourage women in the United States and other industrialized countries to really get out there and exercise a lot, to improve their cardiovascular health and other aspects of their health.

But when they did so, and they really like committed themselves to [exercising], they often experienced disruptions in their reproductive functioning, specifically in their ovarian cycles.

They would notice that maybe they wouldn't have a menstrual bleed, or they'd have a very long cycle before having a menstrual bleed, or even go months without a menstrual bleed. And this became very unnerving because of course, these women were concerned about their fertility and they saw doctors, and many of the doctors said, “You'll probably never be able to conceive again. You've got a serious problem.”

But other doctors said, "No, you know, I think that if you stop exercising so much and, or you know, stop dieting,” which was another phenomenon, “that in fact you'll have normal fecundity." Or the capacity to conceive.

And in fact that's what they found. They found that these women could return to the normal capacity to conceive if they reduced their energetic stress. This idea of putting out lots of energy, using lots of energy or consuming or reducing your caloric intake -- those are all energetic stressors, reducing or changing your energy balance.

But the thing is then, that at the same time, there were studies in a couple of populations outside the United States and they found that women in those populations had lower hormone levels and they said, "Whoa, these women working in these really arduous conditions have lower hormone levels. They must be just like these exercising women in the United States who have disrupted cycles and low hormone levels. So these women won't be able to conceive either just like the exercising women.” So that was the parallel that was made.

But this struck me as a paradox, because you had these women in these really hard conditions working a lot, but we knew they were having lots of babies. And so how could their fertility be impaired?

Some people said, “Well, when their hormones go up occasionally during the year then they might be able to conceive, but most of the time they can't conceive.” And that didn't make sense to me. And so I thought [it] was more likely that what was normal stress, the normal vagaries of life [for] these women in these seemingly difficult conditions, were something they were adapted to -- whereas in Boston or Chicago or other such places, these women were used to a really cushy life. And so they wouldn't be able to conceive if they face an unusual stress.

You can kind of think of women in industrialized countries as hothouse flowers. Everything's always really nice and if [you] just make a small perturbation, just a small change in the environment then they can't grow as well until the conditions they were used to return. In these agrarian populations, things were always that hard and they had to reproduce. That's how evolution works. You reproduce under the conditions you've got. And so they were adapted to those conditions physiologically. Well. this is a nice idea but you have to test it. And that was the reason for my study.

Rhea: What what prompted you to actually conduct this study in Chicago and then to choose Bolivia?

Virginia: Well actually I chose Bolivia first and I chose Bolivia because it is what we call a “natural fertility population,” [and] there are periods when they're working really hard in the farms and there are other periods when they don't have much to eat until the crops come in. And so this was a perfect condition under which I could see life long difficult conditions but also short term acute or short term sharp elevations in energetic stress. So, I could look at both conditions at the same time and that's why I chose Bolivia. And I chose Chicago, because it was a typical American population of women living typical, ordinary industrialized lives and was likely to be very similar to what we'd seen in other such populations.

Rhea: So from what I understand, every other day, you measured a lot of pee, and a lot of saliva, to figure out hormone levels at different points in the cycle? Why?

Virginia: So, the the crux of the question was: Was she getting pregnant at the levels of hormones that were low and seemed to be normal in her population? Or could she only get pregnant when the hormone levels were as high as what we saw in Chicago women when they got pregnant?

So that's the critical comparison.

And so if she couldn't get pregnant at typical levels for her population, then one theory was correct, the energetics theory. But if she could get pregnant then the what we call life history theory or my model, I call it the flexible response model, was correct. So, this required that I collect over 10,000 samples of saliva over the course of two years, and God knows how many gallons of pee… and then have them all assayed, and so that was the comparison. And then in the Chicago women we had a sample that self collected their own samples. These were women intending to get pregnant so they self collected their samples and we had a small sample of 30 women there that we could compare our results to.

Rhea: And did, out of curiosity did any of the women in the studies actually get pregnant within those two years?

Virginia: Yes. So the end result of all of that was that [in] the women, I observed more than 60 conceptions, and the outcome of all of this data collection was that I could see the hormone levels at which these women were actually conceiving, and I could see the hormone levels at which the Chicago women were conceiving. And so, I could then see whether or not they only conceived at the same high[hormone] levels or if the Bolivian women were conceiving at lower levels than the Chicago women.

Well that's what I found.

Very surprising to lots of people. These women at their low hormone levels were successfully conceiving and maintaining their pregnancies all the way to giving birth. I followed these women for two years. I knew what their hormone levels were like when they conceived, as their babies developed, and when their babies were born. So I knew exactly what their hormone levels were. And I could compare them to the Chicago women and I could declare legitimately that these women had perfectly functionally adequate hormone levels even though they were lower than Chicago women and they conceived at those low levels.

Rhea: Right. So from the pee you found out when they got pregnant. And from the spit, you knew their hormone levels at the time of conception. And you found that even though these women in Bolivia had lower hormone levels, they still got pregnant at that lower level.

Virginia: And, they conceived without problems. And so what this means is then that there's no species wide normal level of hormone. There's no one correct hormone level that everyone should have in order to be reproductively healthy or reproductively successful.

That in fact every population has different ranges of what is adequate functionally to conceive, and to be healthy, and that we shouldn't assume that white women in industrialized countries are our standard against which to compare everyone else in the world.

And the reason for this is that there are different factors that contribute to your hormone levels. There's going to be individual genes, there's going to be how much energy you expend and intake, there's going to be the composition of your diet and there's going to be other factors that we're just starting to investigate. But those are four of the most important and because those vary across populations. It's perfectly normal and natural that the hormone levels will vary across populations but that women will conceive at those normal hormone levels in their population.

It's also the case that women are responsive to stress that they experience. So it's not like these Bolivian women could tolerate any level of stress. In fact, when we went through the poorest season where they had to work really hard and had little food, then their hormone levels also would dip down and they would also experience reproductive or ovarian cycle disruption. So their bodies are responding similarly across the entire world's population of women but that doesn't mean they have identical hormones.

Rhea: So, you were right! Different groups of people -- depending on their lifestyle -- have different levels that are considered normal for them. Just like, for example, how someone who sits at a cushy desk job might have a different calorie need than a professional athlete. There is no one universal normal.

This makes me think about hormone based medicines. I was wondering how does this information apply to the way women receive health care? Especially in terms of contraception and actually conceiving?

Virginia: These are really important questions because what it means is that we need to have different hormonal contraceptive formulations, for women who are choosing hormonal contraceptives, that fit women.

For too long, the pharmaceutical industry and others have thought that, and the medical world have thought that, basically there's one normal. And so a small set of formulations of hormonal contraceptives would be the best for everyone. But in fact there are women who have said for a very long time, “I get really bad side effects from this combination of pills or this combination of hormones and therefore I'm going to stop using it because it's just too much trouble.” And they've been told, “No, no, no. This is really all in your head. You will adjust your body will adjust and just tolerate it so that you don't have to become pregnant because after all perhaps that's a harder choice to make.”

In fact, what we need to do is recognize that different populations have different average levels and we need to have more formulations that are suited to those women and we can see that in the data as well.

We see that in populations like Bolivia, they have much higher rates of discontinuing use of the hormonal contraceptive in the first year of use due to their reports of side effects. And so it's not just a theory. We've actually seen it in action. And I've been told, for example by a colleague who worked in Bangladesh, that women would actually cut the pills in half to try to reduce the side effects. But of course this has an unknown effect on the risk of pregnancy. So it's not a great idea, it's not a solution.

We need an appropriate formulation and it's not just across populations, it's also within a population. There's more variation in hormone levels within a population than there is across a population. And that may seem very difficult to to really picture in your mind right now. But the differences between say a Boston woman and a Bolivian woman is about 80 percent Bolivians or about 80 percent of U.S. women. But within the population of Bolivian women and within the population of Chicago women or Boston women or German women, the range of variation in normal cycles is five fold. A woman can be perfectly healthy and have only one fifth the hormone level of somebody who's the highest value in that population. So we have lots of variation within and between populations depending on all these different sorts of factors. And we need to instead of telling women that they should fit the pill, we need to fit the pill to the woman. We need to change our attitude.

Rhea: I'm all for that. I love that. That should be the new slogan for menstruating people everywhere. You mentioned energetic stress before. What about the effects of emotional or mental stress on the menstrual cycle?

Virginia: This is an interesting question because it is a very controversial area of research and there's been data on both sides of that question of whether or not there is enough -- whether or not emotional or psychosocial stress can actually affect reproduction.

I favor the idea that it probably does. I think the data that we have is very compelling. In the best studies done, you see it. The fact of the matter is the first person to really document that kind of stress was a fellow named Sam Wasser looking at baboons and the social dynamics among female baboons and positing that there was a real effective psychosocial stress on reproduction in the baboons and he demonstrated it there. And, this makes sense though, it makes sense that energy is of course important. And so as well as energy, are vitamins of various kinds like iodine deficiency can be a factor in disrupting reproductive function. That makes sense because iodine is very important to proper physiological functioning.

Well, we're social creatures, we need support. We need support through pregnancy we need support to give birth, we're the only primate where it is the most common situation is to have someone assisting us in our birth. Whereas other primates can give birth on their own. We always have somebody assisting us whether it's a mother, a partner, another family member, a midwife as we call them today. There's always, just about always, somebody there. It's a myth that women went off into the wild and had babies by themselves because we have a lot of difficulty giving birth. And so that psychosocial support that sense of being supported is very very important in [a] human life cycle. And having it during this period of pregnancy and birthing is really critical. So it makes sense that your body says if you don't have that, maybe it's not a good time for you to reproduce.

[SPONSOR BREAK]

Announcer: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. The period tracking app, and menstrual health resource, that’s not like the other apps.

How is Clue different? Well, Clue doesn’t sell your data.

Instead, as co-founder and CEO Ida explains, the data is separated from your identity, and given to scientists to help push our understanding of menstrual health into the future.

Ida: This is something we have chosen to do because we believe that we have a very unique responsibility when we govern this very unique data set to also help advance research in female health for the benefit of our users but also the greater public. And we have seen that our users share that notion and that they're willing to share their anonymized data so that we can advance female health research.

Announcer: To support the app that doesn’t sell your data and is fighting for BETTER reproductive science, subscribe to Clue Plus.

Your subscription to Clue Plus also funds the period tracking app that doesn't show you a bunch of ads, and was founded and is led by women.

For more -- head over to Clue.Plus.

Alright, back to the show.

[End of Sponsor Break]

Rhea: Virginia, when you were conducting your study, and looking at women in agrarian communities in Bolivia and then women in Chicago and creating this comparison, what differences did you notice in the menstrual cycles of both populations?

Virginia: Yes of course. In the United States and other industrialized countries in the modern world it's the case that women often do not start reproducing, having babies, until sometime in their 20s. But they've had menarche many years before, they've had their first menstrual cycle, menarche when they're perhaps ten or eleven or twelve or thirteen.

So there's this very long span of time in which they're cycling, month after month, year after year and not reproducing because they're not in a sexual relationship. Then they may have a couple of children in their lifetime. They may breastfeed them for a very short time and then they have menopause. And so through that whole span of time they have had perhaps four or five hundred menstrual cycles and experience the hormonal changes of those over the decades of their life.

In contrast, Bolivian women have menarche more around the age of 14 or 15 or 16. They start having babies around the age of 20. And once they have a baby, then they may breastfeed for anywhere from two to four years, have another baby, do the same. And through their life may have as many as 10 or 12 babies. And so they typically in the course of their lifetime, even if it's just as long as an American woman, they may have only 40 or 50 cycles. In fact, there was one woman you know I was asking all the women in these studies when was your last menstrual cycle when I would first interview her, one woman told me when I was 17 and she was 43.

Rhea: Wow.

Virginia: So she had really always continuously been either pregnant or lactating. She was an exceptional case. But you get the idea this pattern of only 40 or 50 cycles versus four or five hundred cycles is the norm throughout our evolutionary history. Women have not experienced four or five hundred cycles they've experienced only 40 or 50 because it was normal to have babies and to lactate them for a long period of time and then to have another baby to have a late menarche and an early menopause compared to what we see today in industrialized countries.

The implications of this for all this hormonal production and exposure are only beginning to be understood. So for example, we have far higher rates of breast cancer in women in industrialized populations than in Bolivian women or other such women in similar populations. We have a high rates of other kinds of hormone related cancers and other sorts of differences in risk for osteoporosis and for autoimmune diseases and for other conditions that are probably a reflection of the fact that we don't have a lot of babies and we have a lot of exposure to menstrual cycling changes in hormone levels.

Now, I'm not advocating that this means we're obligated to go and have lots of babies. That's not the point at all. But it means is to understand what's going on and therefore devise appropriate lifestyle or health interventions that can mitigate those kinds of problems in a way that is not disruptive. That's not over medicalized. There's nothing wrong with women not having babies anymore than there's anything wrong with women having lots of babies. The point is to create the best health for women whatever their decisions are. And we can't do that unless we know more about what's going on.

Rhea: Virginia, You have made some really great points today and an especially compelling argument in this conversation about the need for further research to better understand the endocrinology of different kinds of people who menstruate around the world. But, what other kinds of research do you think is important, moving forward, to make hormonal therapies more effective for more people?

Virginia: Well I do think that to begin with, we need to understand what the causes of all of this variation is. And that means understanding more about the growth of the girl.

We have concentrated a great many resources on understanding children from the time that they're born until about five years of age. And that's logical because that's a period of high mortality. And so a lot of effort has gone into understanding that period of life. And we put a lot of effort into understanding adult women, particularly women who are going to become moms. There's been a real focus on that.

I think that we need to do two things: First of all, we need to concentrate on the growing girl, the girl who is growing from age 5 through about age 18 and those changes that happen through menarche as she becomes a full adult female. It's surprising how little we know even within one culture, the United States or Germany or Europe and other such industrialized countries. And we know so much less in other populations. And we don't understand that period as well as we need to at all.

The other thing is that we need to appreciate the incredible diversity of women's bodies and needs, and to design medications as well as hormonal contraceptives, to design health care, in response to that. We need to recognize that and do more research instead of trying to pigeonhole every woman in to this old fashioned medical view that women are basically biological clocks that should be running on time and running according to calendars. Women's biology is responsive to the environment, responsive to psychosocial conditions, responsive to her activities and it has evolved to be exactly that. And so these are normal variations that occur in response to the conditions that are all around her and her part of her life. And instead we're trying to pigeonhole her into this narrow view of what a woman's body should be like.

Women are not little clocks.

Rhea: That’s right. I totally agree with you, you’ve made me feel completely empowered that I have all of this amazing energy inside my body.

Thank you so much. Virginia Vitzthum. We thank you for joining us here. She's the senior researcher at the Kinsey Institute and the head of Scientific Research at Clue. Thank you so much for joining us on Hormonal.

Virginia: Thank you very much for your time.

Rhea: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. If you like the podcast, subscribe and rate us five stars on your platform of choice. Or find us on social media!

To support the work here at Clue -- subscribe to Clue Plus. Every cent goes to fund the work here at Clue -- that includes the app and archives of meticulous menstrual health information on Clue’s website. You can find out more about Clue Plus at Clue.Plus.