A podcast about how hormones shape our world.

Latest episode:

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

About Hormonal

Hormones affect everyone and everything: from skin to stress to sports.

But for most of us, they're still a mystery.

Even the way we talk about hormones makes no sense. ("She's hormonal.")

So let's clear some things up. Each week, Rhea Ramjohn is asking scientists, doctors, and experts to break it all down for us.

Subscribe on your favorite platform:

Episodes

- Season 1

- Season 2

Episode 0

August 25, 2020

A Sneak Peek at Season 2

As we work hard on Season 2 of the Hormonal podcast, we’re dropping into your feed with a special request, and a small behind the...

5 min

Episode 1

October 11, 2020

Hot or not? Birth control & sex drive

How birth control affects your sexual desire, self image, and weight fluctuations.

25 min

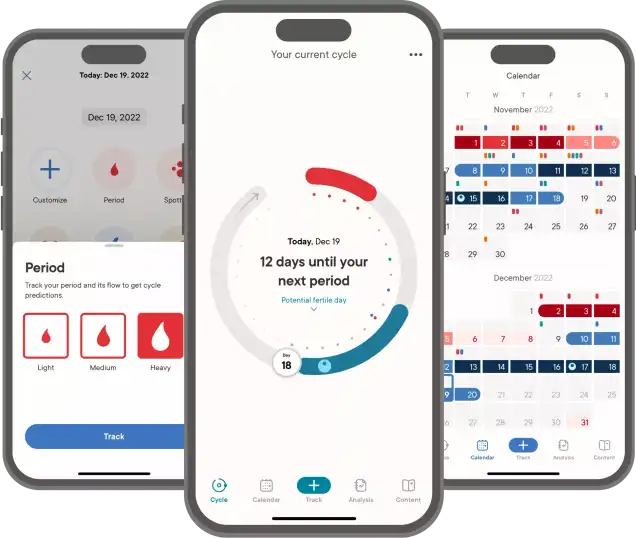

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Episode 2

October 19, 2020

The ABC: Abortion & Birth Control

What’s it like to get an abortion and the surprising ways the pandemic is changing abortion access.

34 min

Episode 3

October 26, 2020

The many sides of side effects

Hormonal birth control: positive, negative, and neutral effects

33 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Reproductive choice and reproductive justice

with Dr. Loretta Ross

Episode 4

November 2, 2020

Reproductive choice and reproductive justice

Accessing birth control against the odds

35 min

Episode 5

November 9, 2020

Happy birthday, birth control

Controversy and celebration on the 60th anniversary of the pill

42 min

Episode 7

November 23, 2020

Risky business: birth control during COVID-19

COVID-19 is changing how we access birth control

30 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

with Lynae Brayboy, Amanda Shea & Hajnalka Hejja

Episode 8

November 30, 2020

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

Clue’s Science Team busts your birth control myths

37 min

Credits

Season 2

Executive Producer: Kassandra Sundt

Host: Rhea Ramjohn

Editorial Help from: Amanda Shea, Steph Liao, Nicole Leeds

Clue Design: Marta Pucci & B.J. Scheckenbach

Web Team: Yomi Eluwande, Jane Parr-Burman, Maddie Sheesley

Special Thanks: Trudie Carter, Ryan Duncan, Aubrey Bryan,

Claudia Taylor, Léna Calvarin, Lynae Brayboy

Mixing and recording help from: Bose Park Productions & Rekorder Studios in Berlin.

About Clue

Clue is a period tracking app that uses data and science to help women and people wih cycles to understand their bodies. It's also a menstrual and reproductive health encyclopedia.

Learn more about the Clue app and check out what Clue is doing to advance menstrual health research.

Rhea Ramjohn,

host of the Hormonal Podcast

Rhea Ramjohn,

host of the Hormonal Podcast

Your Host

The more knowledge we have about our hormones, our medical & menstrual care, and our reproductive rights, the more we empower ourselves and one another.

Hormonal has offered me the true privilege of speaking with people who have the expertise on the scientific knowledge about our hormones and cycles, as well as those sharing their lived experiences, caring for people with menstruation and how, all combined, shapes our lives everyday.

Gathering facts as well as personal stories are so vital to our understanding of our health, our his/herstories, and our cultures. I deem it a privilege because we haven't had many platforms nor opportunities for menstrual health information being broadly accessible.

Episode 1

Grains of Salt: Hormone History in the Modern Age

Grains of Salt: Hormone History in the Modern Age

We go into the wayback machine to look at the history of hormones.

About

We are going in the wayback machine to take a peek at where some of our wild ideas about hormones came from.

Randi Epstein is a doctor, a medical writer and the author of: “Aroused: The History of Hormones and How They Control Just About Everything,” where she explores nearly one hundred years of hormone research. Randi takes us through the history and etymology of the word hormone and how these tiny particles in the body were discovered.

Transcript

This transcript and interview were edited for clarity.

Rhea Ramjohn: Hi, it’s Rhea Ramjohn and you’re listening to Hormonal, brought to you by Clue. Clue is the period tracking app and menstrual encyclopedia where you can get the answers to all of your questions, like what’s up with discharge? What are the differences between cervical fluid, arousal fluid, and vaginal discharge?

Here on Hormonal, we’re looking to make a podcast that has the kind of conversations that we have every single day at Clue. The kind of deep dive into science that makes you go “Ohhhh, so that’s why I do that every month.” Or, “Shut the front door! That is COMPLETELY UNFAIR.”

And that’s why we’re looking at hormones all season long.

Everyone has them. But they’re deeply misunderstood. How many times have you heard, “Ugh, she’s so hormonal today.” Too many times! Yet, you’d never hear that about a man, even though they have hormones just like everyone else.

Hormones are wrapped up in mystery, cultural paranoia, and of course science. And today, we’re going to get in the way back machine, and take a peak at where some of these wild ideas came from.

Joining us now is Randi Epstein. She’s a doctor, a medical writer and the author of: “Aroused: The History of Hormones and How They Control Just About Everything.”

Randi, thanks for joining us on Hormonal.

Randi Epstein: Oh, I'm thrilled to be here.

Rhea: I really enjoyed your book especially when you talk about the nearly one hundred years of hormone research. You start off with the story of a woman named Blanche Gray who, you said, “lived on the wrong side of scientific discovery.” Tell us more about her and tell us about her case and what you meant by this in regards to hormone research.

Randi: She’s not really where it all began. She's before it really all began. And poor Blanche Gray. I dug her up from some old newspaper articles in the late eighteen hundreds, [she] was born in Detroit and ended up making her way into the circus circuit in the late 1800s. Why? Because she was born, as they said at a fat baby and just kept getting fatter and fatter. She ran off to the circus to be the fat lady in the circus. The way, it's a horrible history, the way we had in circuses tall men and bearded ladies and the fat woman. She ended up becoming famous for being known as the fat bride. She ended up dying at a very young age.

Why is she in my story? Because to me she represents, as some doctors were saying at the time, someone who probably had a glandular issue. She should have been seen by doctors, they were saying, not been in the circus. And yet this was 1883. The doctors couldn't have done anything for her. They would have used her sort of like in the circus. They would have eyed her and maybe tried to wait until she died to dissect her glands.

I write about that after she died, knowing that there was a lot of body snatchers in those days -- people that would dig up bodies from the grave and sell them off to researchers so they could study them, they had armed guards at her funeral just so that no one would try to sneak her body off to nearby hospitals and sell her to researchers.

So, I use this story to tell about what was going on in the 1800s. What was going on before the word “hormone” was even invented to describe this field? There were some early research about looking at what are the, what are the testes do? What do the ovaries do? What does the pituitary gland do? The one that's in your brain. The adrenals, that's on your kidneys. But the fascinating thing was in the late 1800s, the adrenal guys weren't talking to the ovary people, who weren't talking to the testes people. They didn't see these secretions, these glands, as one field. It would be like saying to neurosurgeons and dentists: “Oh, you should be one field.” It was really seen as a completely different body parts and we had no idea.

And it wasn't really until 1905 when these British scientists said, “You know what. There is this commonality between all the glands in the body.” And they came up with the name hormone. And I'm happy to explain to you how we came up with the name “hormone” for hormones.

Rhea: I am actually dying to know you know as a writer. I'm really interested in the etymology of words so tell us, where did the word hormone come from? And how were these tiny, can I call them particles in the body discovered?

Randi: Sure. So the word hormone was invented or came up in 1905. So we're not talking ancient history. My grandmother was born in 1900, in 1905, these two doctors, they came up with this concept that not every message in the body has to travel along nerves, and that's how we thought about the body before. Every message had to travel along nerves.

Once we discovered hormones, it was as if they were trying to explain that your body has this internal Wi-Fi. But this was 1905. We didn't have Wi-Fi then. So it was a very bizarre concept. And I'd like to think of it as like your internal Wi-Fi because the way, when I write an e-mail I know or I hope that it's going to go out into cyberspace and hit its target, just the person I've sent it to. It's not just going to be all over for anyone that wants to see it or it's not supposed to be there for anyone to see.

Hormones are tiny packets of chemicals that are released from a gland, and unlike oxygen that can flow through the blood and just knocks about and is used anywhere, hormones hit a specific target. So for instance, we all know people that are diabetics. They do not have to get their insulin into their pancreas. They can take a shot of insulin anywhere and it will go to where it's needed. Pretty revolutionary concept. We take it for granted now, but it's pretty revolutionary concept at the time. So they needed a name. They thought, “Well internal secretion?” That's what they were called “secretions.” That doesn’t say much...

Rhea: Oohhh…

Randi: That doesn't seem like you know, it sounds like your glands are sponges and just stuff is just oozing out. That doesn't describe the thrill of a tiny packet of information that goes out of one gland and goes directly to its target. That could be brain, a gland in the brain to the ovary. It could be to the adrenals. That's fascinating. So they did what doctors do when they need a name. They thought, “We need something from the Greek because that makes it sound you know highfalutin.” Like internal secretion didn't work. There were other kind of things, glandular juices. That doesn't sound very medical...

Rhea: Juices doesn't sound very good. No.

Randi: No, no, no, no! So they went to a friend of theirs at Cambridge University, a classics professor and said, “What's a word that means to excite or to arouse?” And this professor said, "Well, how about something along the lines from the Greek of "Hor- Moa,” which means to arouse?”

So they went back to their meeting that night in London and said, gave this long long lecture and then said, “Hormones as we shall call them.”

Rhea: So the science or the research itself isn't that old. So, tell us a little bit more about the common thinking during that time about the ovaries, the uterus and the hormones that we now know lend themselves to menstruation.

Randi: Well, you know it took a while to figure out the menstrual cycle there was a while when we thought your most fertile period was while you were menstruating. That probably wasn't helpful before the days of contraception for women or even for those that were trying to get pregnant. We finally got it all figured out, and it still is really complicated, and there's things we still don't know, but, we do know it's this ebb and flow of estrogen and progesterone which of course and knowing this has led to the birth control pill, which has its own rocky history, and treatment for menopause today.

Rhea: So tell us about the early days of the science around estrogen and testosterone.

Randi: Well, going back in time. There was a huge interest in trying to figure out what were these chemicals coming out of the ovary? What were these chemicals coming out of testes? So, we have this history for instance in testosterone of thinking, “Oh, it has to do with anything aggressive or anything, manly…” which was thought of thinking more clearly, getting ahead in business. There were fears in the 1920s and 1930s, once we had estrogen and testosterone and progesterone isolated, that not only would this maybe... yes, okay great. We could help with fertility. We could help with irregular periods. But then people were like, “Oh wait are we gonna like... What about these suffragettes? These women that were so careerist or thinking they could work, are they gonna want sort of male hormones? Are they going to take over the world? What are we going to destroy their “maternal,” their “natural” instinct to want to stay home and raise kids?” Which estrogen and progesterone apparently was deemed to do.

What I find fascinating about that time period, but I also think it extends to every time period is that we get these kernels of truth in science. You know, we did purify estrogen. We did purify progesterone. We did then purify testosterone. But when we look at what the implications are, that's when you get cultural influences into science how we interpret the data. And we have this weird history of sometimes using seeds of science to back sort of cultural claims or things that we want to be truthful.

Rhea: Well, I understand that after it was discovered that the ovaries release estrogen and progesterone, there was apparently a new fad that popped up at that time of “ovary potions?”

Randi: Oh sure! There were things that were like ground up rabbits ovaries. You know, the thinking was that if the ovaries held things that were female, which of course then was, what was female? Making babies, being attractive to men, you know, being the charming housewife. If perhaps maybe you weren't feeling all that, and wanting, the urge to have children, if you weren't feeling that way then there were all sorts of potions.

So, some of the potions that even go back to the early 1900s, before we had isolated the hormones but we knew the ovaries did this kind of stuff. Maybe they had dried up rabbits ovaries in it? Maybe they just said they did but they didn't. You know, maybe it was sugar water!

[Sponsor Break]

Announcer: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. The period tracking app, and menstrual health resource, that takes all parts of your cycle seriously.

Ida is the co-founder and CEO of Clue. And she says unlike some other period tracking apps, Clue does not sell your data.

Ida: I believe that you can only really do anything meaningful for people if they trust you. You know we are asking people to share their most intimate data with us, so that we can give them something valuable back. So we are asking for a lot of trust and I feel a huge sense of responsibility to govern that data.

Announcer: To support the app that doesn’t sell your data, subscribe to Clue Plus.

Your subscription to Clue Plus also funds the period tracking app that doesn't show you a bunch of ads, and was founded and is led by women.

For more information -- check out Clue.Plus.

Alright, back to the show.

[End of Sponsor Break]

Rhea: After the discovery of these glands, that’s when hormones were actually synthesized. But, it was still really hard to measure them in the body. This would be in about the 1950s, and you write in your book that doctors were known to play, pretty fast and loose with these hormones, right? You have an example of young teenagers, if they weren’t growing fast enough according to some chart, a doctor would just give them human growth hormone?

Randi: Absolutely. And you know there were some doctors that fall into the charlatan category. They knew that there was a market to be had and that they could market things for female complaints or male complaints. And then there were other doctors that I think were well-meaning but they were just kind of wrong. And, you know, it's hard to say who is who. You don't really know someone's motives. But there was a lot, yes, a lot of medicine men, and a few medicine women, the few that there were, promoting a lot of cures.

And to me, the interesting thing is not so much that these doctors were promoting stuff, but that we constantly have this yearning throughout history, and even today, of how can we control our hormones?

You know, the hormones control us. They're responsible for physical changes, for going through puberty, for our moods, for our appetite, for our libido. And we just can't help it. We want desperately to control our hormones. We want, we want to take the pill that's going to keep our libido up and our skin looking young and all the things that go along with it.

And we do know more and we're learning more and I think we are getting ahead, and the field of endocrinology is fascinating. But throughout the ages we, it's just big business. We can't help but go to the store and say, “Oh, maybe this can’t hurt. But it does show that if I take this it might boost my libido.”

Rhea: Right. Right. And around the same time period as the “ovary potions” -- there was even a fad of of doctors, like implanting testes, animal testes into people and sort of experimenting with glands? What did they think that this was going to accomplish?

Randi: Well… OK. So the gland business was huge. You know, you get a little testes, you know, if you have two testes, why not three? Why not more? And we were taking like ones from from monkeys and apes and goats and getting them implanted in. And now looking back, people think they just kind of disintegrated.

The other thing that was hugely popular around the same time, that was promoted by a neuroscientist and he felt that it was much better and much simpler than any of these gland operations, he promoted for men, he didn't call it this but it was basically a vasectomy to boost your libido. Spoiler alert. I'll tell you the end of the story, is that vasectomies do not boost your libido. They do prevent contraception. They do prevent you from impregnating someone. But they don't boost your libido.

Rhea: You write that once we start to enter the 1950s, that doctors start to get a handle on Hormones. But they weren’t measurable. So they were still using them a bit helter skelter. Tell us a bit about this period.

Randi: In terms of measuring hormones I really consider this a revolution in 20th century medicine and I never use the word revolution. I mean, I do it once when I talk about when we were able to measure hormones for the first time. So yes, you're so right.

The thinking was really up until the late 1950s that hormones were too scarce to measure. I mean they really were talking... When we talk about hormones, we're not talking like a cup of sugar amount. We're talking like a teeny, like one grain of salt thrown into the ocean and it has a huge impact. They really come in tiny chemical packets that were thought that they were too small and sparse to measure.

So once we could measure hormones that meant yes, if you had a growth hormone deficiency you could go to the doctor and the doctor could measure your level of growth hormone. And now a days because of this technique that was developed in the late 1950s we can measure hormones down to the billionth of a gram. That's billionth with a B.

You know, the same technique that measured hormones is used to detect HIV in the blood, for fertility treatments, for cancer markers. Anything that we thought was immeasurable. This technique is used for. So it's seriously revolutionized modern medicine.

Rhea: Earlier you spoke about contraception. And I want to talk about a very popular form of birth control — the pill. When was the pill invented?

Randi: Well, you know it's interesting. It’s really the birth control pill, no surprise, is really a history of women of how we treat women through in research.

So the birth control pill came about and it's a long fascinating story that includes some horrific testing on women in Puerto Rico and giving them massive high doses, and women complaining, and doctors not listening to their complaints. And then, it also combines history at Harvard [University] where the doctor doing the research basically had to say that he was doing research on fertility. Which he was. But the thinking was he's trying to make something to help infertile women, because he was Catholic and it was seen as it was seen as not such a great thing to make a contraception. You know, it was against the church and people worried. Hormonal contraception, just sounded… Also would this lead to wild women? What would this mean? If you could take a pill and prevent pregnancy?

So it had all this stigma around it and secrecy and some very unethical science, leading up to the FDA approval of the original birth control pill. That [pill] was ten times more hormones than we have today. There were women at the time saying, “I have massive headaches. My breasts are really swollen." There were women that got deadly strokes and it was all kind of ignored. No one was really paying attention at first. If you went to your doctor and said, “I have a massive headache,” he would be like, "Well at least you know you're not going to get pregnant."

At the same time, I found this radio interview, in the early 1960s, with a doctor that was experimenting with a birth control pill for men. And his experiment lasted about a week and then he said, “These men told me they felt like they had a shot of bourbon! I had to end the trial! Men can't feel out of it. They can't, how are they got their day of work?” So they stopped the trial.

It wasn't until a group of feminists, you know “women's libbers” they call them, you know, from the women's liberation, stormed in on congressional testimony, and in, you know, and this was going back after the pill was around for 10 years and started saying we want, one, lower doses. And they also said, “We want warning labels. You have to warn women of the increased risk of stroke!” And now we know that there really is an increased risk of stroke, particularly among women who smoke.

But these were not doctors, these were women demanding that their doctors pay attention to their symptoms. So, I think the history of the birth control pill is fascinating because it shows that we need female activism. That we have to really push for things that we want, and to make sure that doctors hear what we have to say. I think it is changing, there's a lot more female doctors now but that doesn't mean that we have to be quieter. We still have to be noisy. We still have to have doctors hear our complaints, to push for better pills now.

Rhea: Looking in the last 50 years or so since then, what has been the state of hormone research? Especially as it relates to menstruation and cycles? And where have there been advancements?

Randi: We've made huge advances, but I still think that we have a long way to go. I mean now we're looking into things like an artificial uterus or how to help women get pregnant who've had a hysterectomy or have problems there.

I think we do need more research into endometriosis. We have more insights into endometriosis -- which is when the cells that are in your uterus for some reason are outside your uterus. Women that suffer from endometriosis have incapacitating pain during their periods. Some women have these cells end up in their lung. They get huge blood clots. So, we need a lot more research into endometriosis. We need a lot more awareness.

So, I think we've made huge strides in understanding more about endometriosis, understanding more about fertility. People that 50 years ago would never have been able to get pregnant, have now been able to enjoy pregnancy and have children.

But, but we have a long way to go. I think we need, I think we still need to be able to use the tools. We can measure hormones now, we can see things in the body that we've never been able to see before we can go down into the genetics. So we’re at a very exciting time in terms of understanding fertility. And now the other fascinating thing is we're getting more and more insights into neuroendocrinology. So what do we know about hormones? And hormones and moods? What do we know about premenstrual tension? What do we know about perimenopause? What can we do to help women that are going through these ups and downs that really do suffer, to make life higher quality for them during these times?

Rhea: Randi Epstein joins us from New York City. She's a doctor and a medical writer and the author of “Aroused: The History of Hormones and How They Control Just About Everything.” Randi thank you so much for joining us on hormonal.

Randi: This was so much fun. Thank you. Thanks for inviting me.

Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. If you like the podcast, subscribe and rate us five stars on your platform of choice. Or find us on social media!

To support the work here at Clue -- subscribe to Clue Plus. Every cent goes towards informing you. That includes the app and the archives of meticulous menstrual health information on the website. Including the answers to the question at the top of the show. Check the links in the show notes for more.

You can find out more about Clue Plus at Clue.Plus.

Episode 1

September 30, 2019

Grains of Salt: Hormone History in the Modern Age

We go into the wayback machine to look at the history of hormones.

About

We are going in the wayback machine to take a peek at where some of our wild ideas about hormones came from.

Randi Epstein is a doctor, a medical writer and the author of: “Aroused: The History of Hormones and How They Control Just About Everything,” where she explores nearly one hundred years of hormone research. Randi takes us through the history and etymology of the word hormone and how these tiny particles in the body were discovered.

"In terms of measuring hormones I really consider this a revolution in 20th century medicine and I never use the word revolution. I mean, I do it once when I talk about when we were able to measure hormones for the first time. So yes, you're so right."

Rhea Ramjohn: Hi, it’s Rhea Ramjohn and you’re listening to Hormonal, brought to you by Clue. Clue is the period tracking app and menstrual encyclopedia where you can get the answers to all of your questions, like what’s up with discharge? What are the differences between cervical fluid, arousal fluid, and vaginal discharge?

Here on Hormonal, we’re looking to make a podcast that has the kind of conversations that we have every single day at Clue. The kind of deep dive into science that makes you go “Ohhhh, so that’s why I do that every month.” Or, “Shut the front door! That is COMPLETELY UNFAIR.”

And that’s why we’re looking at hormones all season long.

Everyone has them. But they’re deeply misunderstood. How many times have you heard, “Ugh, she’s so hormonal today.” Too many times! Yet, you’d never hear that about a man, even though they have hormones just like everyone else.

Hormones are wrapped up in mystery, cultural paranoia, and of course science. And today, we’re going to get in the way back machine, and take a peak at where some of these wild ideas came from.

Joining us now is Randi Epstein. She’s a doctor, a medical writer and the author of: “Aroused: The History of Hormones and How They Control Just About Everything.”

Randi, thanks for joining us on Hormonal.

Randi Epstein: Oh, I'm thrilled to be here.

Rhea: I really enjoyed your book especially when you talk about the nearly one hundred years of hormone research. You start off with the story of a woman named Blanche Gray who, you said, “lived on the wrong side of scientific discovery.” Tell us more about her and tell us about her case and what you meant by this in regards to hormone research.

Randi: She’s not really where it all began. She's before it really all began. And poor Blanche Gray. I dug her up from some old newspaper articles in the late eighteen hundreds, [she] was born in Detroit and ended up making her way into the circus circuit in the late 1800s. Why? Because she was born, as they said at a fat baby and just kept getting fatter and fatter. She ran off to the circus to be the fat lady in the circus. The way, it's a horrible history, the way we had in circuses tall men and bearded ladies and the fat woman. She ended up becoming famous for being known as the fat bride. She ended up dying at a very young age.

Why is she in my story? Because to me she represents, as some doctors were saying at the time, someone who probably had a glandular issue. She should have been seen by doctors, they were saying, not been in the circus. And yet this was 1883. The doctors couldn't have done anything for her. They would have used her sort of like in the circus. They would have eyed her and maybe tried to wait until she died to dissect her glands.

I write about that after she died, knowing that there was a lot of body snatchers in those days -- people that would dig up bodies from the grave and sell them off to researchers so they could study them, they had armed guards at her funeral just so that no one would try to sneak her body off to nearby hospitals and sell her to researchers.

So, I use this story to tell about what was going on in the 1800s. What was going on before the word “hormone” was even invented to describe this field? There were some early research about looking at what are the, what are the testes do? What do the ovaries do? What does the pituitary gland do? The one that's in your brain. The adrenals, that's on your kidneys. But the fascinating thing was in the late 1800s, the adrenal guys weren't talking to the ovary people, who weren't talking to the testes people. They didn't see these secretions, these glands, as one field. It would be like saying to neurosurgeons and dentists: “Oh, you should be one field.” It was really seen as a completely different body parts and we had no idea.

And it wasn't really until 1905 when these British scientists said, “You know what. There is this commonality between all the glands in the body.” And they came up with the name hormone. And I'm happy to explain to you how we came up with the name “hormone” for hormones.

Rhea: I am actually dying to know you know as a writer. I'm really interested in the etymology of words so tell us, where did the word hormone come from? And how were these tiny, can I call them particles in the body discovered?

Randi: Sure. So the word hormone was invented or came up in 1905. So we're not talking ancient history. My grandmother was born in 1900, in 1905, these two doctors, they came up with this concept that not every message in the body has to travel along nerves, and that's how we thought about the body before. Every message had to travel along nerves.

Once we discovered hormones, it was as if they were trying to explain that your body has this internal Wi-Fi. But this was 1905. We didn't have Wi-Fi then. So it was a very bizarre concept. And I'd like to think of it as like your internal Wi-Fi because the way, when I write an e-mail I know or I hope that it's going to go out into cyberspace and hit its target, just the person I've sent it to. It's not just going to be all over for anyone that wants to see it or it's not supposed to be there for anyone to see.

Hormones are tiny packets of chemicals that are released from a gland, and unlike oxygen that can flow through the blood and just knocks about and is used anywhere, hormones hit a specific target. So for instance, we all know people that are diabetics. They do not have to get their insulin into their pancreas. They can take a shot of insulin anywhere and it will go to where it's needed. Pretty revolutionary concept. We take it for granted now, but it's pretty revolutionary concept at the time. So they needed a name. They thought, “Well internal secretion?” That's what they were called “secretions.” That doesn’t say much...

Rhea: Oohhh…

Randi: That doesn't seem like you know, it sounds like your glands are sponges and just stuff is just oozing out. That doesn't describe the thrill of a tiny packet of information that goes out of one gland and goes directly to its target. That could be brain, a gland in the brain to the ovary. It could be to the adrenals. That's fascinating. So they did what doctors do when they need a name. They thought, “We need something from the Greek because that makes it sound you know highfalutin.” Like internal secretion didn't work. There were other kind of things, glandular juices. That doesn't sound very medical...

Rhea: Juices doesn't sound very good. No.

Randi: No, no, no, no! So they went to a friend of theirs at Cambridge University, a classics professor and said, “What's a word that means to excite or to arouse?” And this professor said, "Well, how about something along the lines from the Greek of "Hor- Moa,” which means to arouse?”

So they went back to their meeting that night in London and said, gave this long long lecture and then said, “Hormones as we shall call them.”

Rhea: So the science or the research itself isn't that old. So, tell us a little bit more about the common thinking during that time about the ovaries, the uterus and the hormones that we now know lend themselves to menstruation.

Randi: Well, you know it took a while to figure out the menstrual cycle there was a while when we thought your most fertile period was while you were menstruating. That probably wasn't helpful before the days of contraception for women or even for those that were trying to get pregnant. We finally got it all figured out, and it still is really complicated, and there's things we still don't know, but, we do know it's this ebb and flow of estrogen and progesterone which of course and knowing this has led to the birth control pill, which has its own rocky history, and treatment for menopause today.

Rhea: So tell us about the early days of the science around estrogen and testosterone.

Randi: Well, going back in time. There was a huge interest in trying to figure out what were these chemicals coming out of the ovary? What were these chemicals coming out of testes? So, we have this history for instance in testosterone of thinking, “Oh, it has to do with anything aggressive or anything, manly…” which was thought of thinking more clearly, getting ahead in business. There were fears in the 1920s and 1930s, once we had estrogen and testosterone and progesterone isolated, that not only would this maybe... yes, okay great. We could help with fertility. We could help with irregular periods. But then people were like, “Oh wait are we gonna like... What about these suffragettes? These women that were so careerist or thinking they could work, are they gonna want sort of male hormones? Are they going to take over the world? What are we going to destroy their “maternal,” their “natural” instinct to want to stay home and raise kids?” Which estrogen and progesterone apparently was deemed to do.

What I find fascinating about that time period, but I also think it extends to every time period is that we get these kernels of truth in science. You know, we did purify estrogen. We did purify progesterone. We did then purify testosterone. But when we look at what the implications are, that's when you get cultural influences into science how we interpret the data. And we have this weird history of sometimes using seeds of science to back sort of cultural claims or things that we want to be truthful.

Rhea: Well, I understand that after it was discovered that the ovaries release estrogen and progesterone, there was apparently a new fad that popped up at that time of “ovary potions?”

Randi: Oh sure! There were things that were like ground up rabbits ovaries. You know, the thinking was that if the ovaries held things that were female, which of course then was, what was female? Making babies, being attractive to men, you know, being the charming housewife. If perhaps maybe you weren't feeling all that, and wanting, the urge to have children, if you weren't feeling that way then there were all sorts of potions.

So, some of the potions that even go back to the early 1900s, before we had isolated the hormones but we knew the ovaries did this kind of stuff. Maybe they had dried up rabbits ovaries in it? Maybe they just said they did but they didn't. You know, maybe it was sugar water!

[Sponsor Break]

Announcer: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. The period tracking app, and menstrual health resource, that takes all parts of your cycle seriously.

Ida is the co-founder and CEO of Clue. And she says unlike some other period tracking apps, Clue does not sell your data.

Ida: I believe that you can only really do anything meaningful for people if they trust you. You know we are asking people to share their most intimate data with us, so that we can give them something valuable back. So we are asking for a lot of trust and I feel a huge sense of responsibility to govern that data.

Announcer: To support the app that doesn’t sell your data, subscribe to Clue Plus.

Your subscription to Clue Plus also funds the period tracking app that doesn't show you a bunch of ads, and was founded and is led by women.

For more information -- check out Clue.Plus.

Alright, back to the show.

[End of Sponsor Break]

Rhea: After the discovery of these glands, that’s when hormones were actually synthesized. But, it was still really hard to measure them in the body. This would be in about the 1950s, and you write in your book that doctors were known to play, pretty fast and loose with these hormones, right? You have an example of young teenagers, if they weren’t growing fast enough according to some chart, a doctor would just give them human growth hormone?

Randi: Absolutely. And you know there were some doctors that fall into the charlatan category. They knew that there was a market to be had and that they could market things for female complaints or male complaints. And then there were other doctors that I think were well-meaning but they were just kind of wrong. And, you know, it's hard to say who is who. You don't really know someone's motives. But there was a lot, yes, a lot of medicine men, and a few medicine women, the few that there were, promoting a lot of cures.

And to me, the interesting thing is not so much that these doctors were promoting stuff, but that we constantly have this yearning throughout history, and even today, of how can we control our hormones?

You know, the hormones control us. They're responsible for physical changes, for going through puberty, for our moods, for our appetite, for our libido. And we just can't help it. We want desperately to control our hormones. We want, we want to take the pill that's going to keep our libido up and our skin looking young and all the things that go along with it.

And we do know more and we're learning more and I think we are getting ahead, and the field of endocrinology is fascinating. But throughout the ages we, it's just big business. We can't help but go to the store and say, “Oh, maybe this can’t hurt. But it does show that if I take this it might boost my libido.”

Rhea: Right. Right. And around the same time period as the “ovary potions” -- there was even a fad of of doctors, like implanting testes, animal testes into people and sort of experimenting with glands? What did they think that this was going to accomplish?

Randi: Well… OK. So the gland business was huge. You know, you get a little testes, you know, if you have two testes, why not three? Why not more? And we were taking like ones from from monkeys and apes and goats and getting them implanted in. And now looking back, people think they just kind of disintegrated.

The other thing that was hugely popular around the same time, that was promoted by a neuroscientist and he felt that it was much better and much simpler than any of these gland operations, he promoted for men, he didn't call it this but it was basically a vasectomy to boost your libido. Spoiler alert. I'll tell you the end of the story, is that vasectomies do not boost your libido. They do prevent contraception. They do prevent you from impregnating someone. But they don't boost your libido.

Rhea: You write that once we start to enter the 1950s, that doctors start to get a handle on Hormones. But they weren’t measurable. So they were still using them a bit helter skelter. Tell us a bit about this period.

Randi: In terms of measuring hormones I really consider this a revolution in 20th century medicine and I never use the word revolution. I mean, I do it once when I talk about when we were able to measure hormones for the first time. So yes, you're so right.

The thinking was really up until the late 1950s that hormones were too scarce to measure. I mean they really were talking... When we talk about hormones, we're not talking like a cup of sugar amount. We're talking like a teeny, like one grain of salt thrown into the ocean and it has a huge impact. They really come in tiny chemical packets that were thought that they were too small and sparse to measure.

So once we could measure hormones that meant yes, if you had a growth hormone deficiency you could go to the doctor and the doctor could measure your level of growth hormone. And now a days because of this technique that was developed in the late 1950s we can measure hormones down to the billionth of a gram. That's billionth with a B.

You know, the same technique that measured hormones is used to detect HIV in the blood, for fertility treatments, for cancer markers. Anything that we thought was immeasurable. This technique is used for. So it's seriously revolutionized modern medicine.

Rhea: Earlier you spoke about contraception. And I want to talk about a very popular form of birth control — the pill. When was the pill invented?

Randi: Well, you know it's interesting. It’s really the birth control pill, no surprise, is really a history of women of how we treat women through in research.

So the birth control pill came about and it's a long fascinating story that includes some horrific testing on women in Puerto Rico and giving them massive high doses, and women complaining, and doctors not listening to their complaints. And then, it also combines history at Harvard [University] where the doctor doing the research basically had to say that he was doing research on fertility. Which he was. But the thinking was he's trying to make something to help infertile women, because he was Catholic and it was seen as it was seen as not such a great thing to make a contraception. You know, it was against the church and people worried. Hormonal contraception, just sounded… Also would this lead to wild women? What would this mean? If you could take a pill and prevent pregnancy?

So it had all this stigma around it and secrecy and some very unethical science, leading up to the FDA approval of the original birth control pill. That [pill] was ten times more hormones than we have today. There were women at the time saying, “I have massive headaches. My breasts are really swollen." There were women that got deadly strokes and it was all kind of ignored. No one was really paying attention at first. If you went to your doctor and said, “I have a massive headache,” he would be like, "Well at least you know you're not going to get pregnant."

At the same time, I found this radio interview, in the early 1960s, with a doctor that was experimenting with a birth control pill for men. And his experiment lasted about a week and then he said, “These men told me they felt like they had a shot of bourbon! I had to end the trial! Men can't feel out of it. They can't, how are they got their day of work?” So they stopped the trial.

It wasn't until a group of feminists, you know “women's libbers” they call them, you know, from the women's liberation, stormed in on congressional testimony, and in, you know, and this was going back after the pill was around for 10 years and started saying we want, one, lower doses. And they also said, “We want warning labels. You have to warn women of the increased risk of stroke!” And now we know that there really is an increased risk of stroke, particularly among women who smoke.

But these were not doctors, these were women demanding that their doctors pay attention to their symptoms. So, I think the history of the birth control pill is fascinating because it shows that we need female activism. That we have to really push for things that we want, and to make sure that doctors hear what we have to say. I think it is changing, there's a lot more female doctors now but that doesn't mean that we have to be quieter. We still have to be noisy. We still have to have doctors hear our complaints, to push for better pills now.

Rhea: Looking in the last 50 years or so since then, what has been the state of hormone research? Especially as it relates to menstruation and cycles? And where have there been advancements?

Randi: We've made huge advances, but I still think that we have a long way to go. I mean now we're looking into things like an artificial uterus or how to help women get pregnant who've had a hysterectomy or have problems there.

I think we do need more research into endometriosis. We have more insights into endometriosis -- which is when the cells that are in your uterus for some reason are outside your uterus. Women that suffer from endometriosis have incapacitating pain during their periods. Some women have these cells end up in their lung. They get huge blood clots. So, we need a lot more research into endometriosis. We need a lot more awareness.

So, I think we've made huge strides in understanding more about endometriosis, understanding more about fertility. People that 50 years ago would never have been able to get pregnant, have now been able to enjoy pregnancy and have children.

But, but we have a long way to go. I think we need, I think we still need to be able to use the tools. We can measure hormones now, we can see things in the body that we've never been able to see before we can go down into the genetics. So we’re at a very exciting time in terms of understanding fertility. And now the other fascinating thing is we're getting more and more insights into neuroendocrinology. So what do we know about hormones? And hormones and moods? What do we know about premenstrual tension? What do we know about perimenopause? What can we do to help women that are going through these ups and downs that really do suffer, to make life higher quality for them during these times?

Rhea: Randi Epstein joins us from New York City. She's a doctor and a medical writer and the author of “Aroused: The History of Hormones and How They Control Just About Everything.” Randi thank you so much for joining us on hormonal.

Randi: This was so much fun. Thank you. Thanks for inviting me.

Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. If you like the podcast, subscribe and rate us five stars on your platform of choice. Or find us on social media!

To support the work here at Clue -- subscribe to Clue Plus. Every cent goes towards informing you. That includes the app and the archives of meticulous menstrual health information on the website. Including the answers to the question at the top of the show. Check the links in the show notes for more.

You can find out more about Clue Plus at Clue.Plus.